How to recognize Finnish design lighting—their value can reach hundreds of thousands

Finnish design lamps from the 1940s to the 1960s are highly valued and fit beautifully in today’s homes. But who designed and produced them?

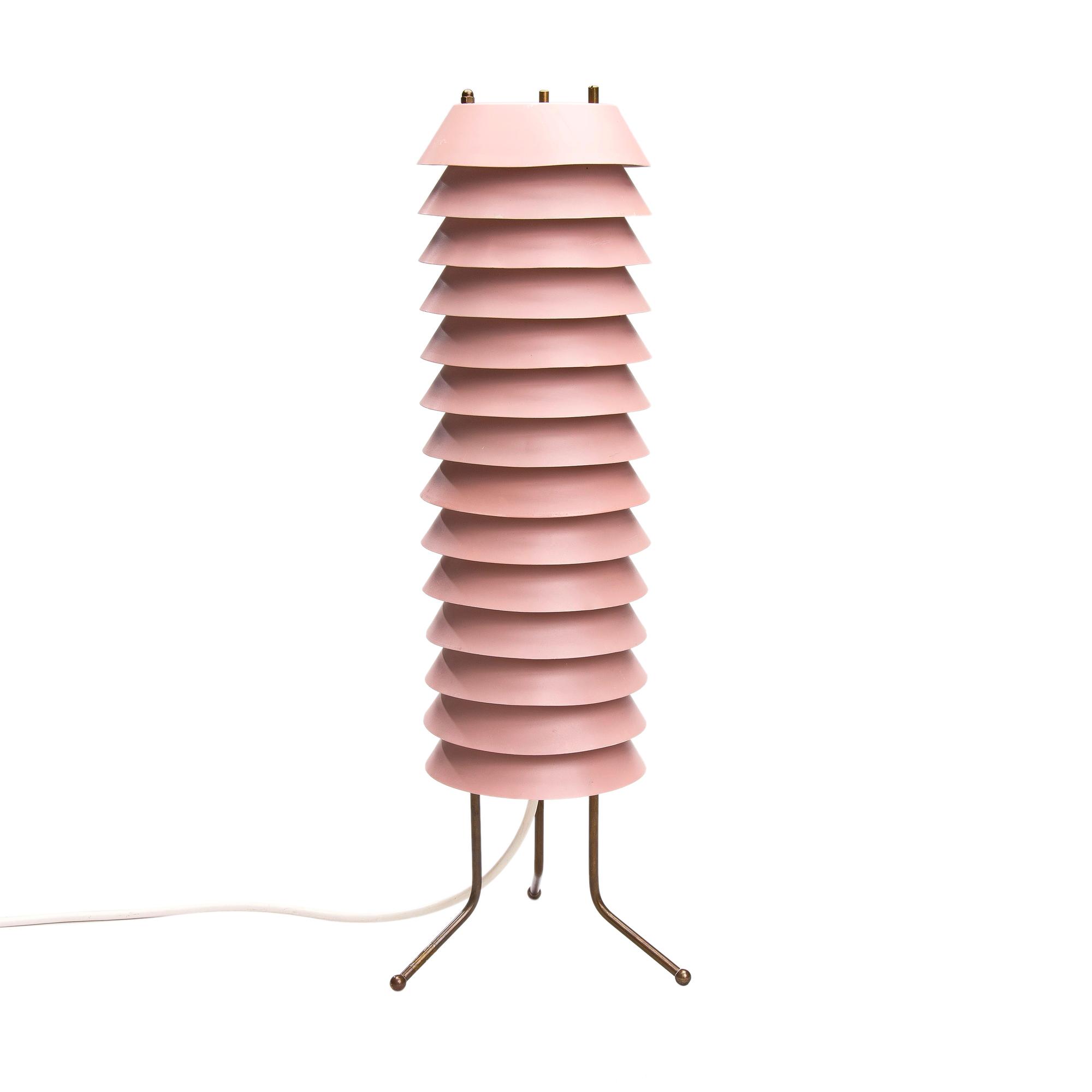

Brass, mouth-blown glass, silk, leather, copper, fine wood, and a brand-new material called Perspex. In the 1950s and 1960s, these refined materials and innovative forms made light fixtures stand out—and they’re just as at home in today’s interiors.

After World War II, when Finland started producing light fixtures on an industrial scale, nearly everything was in short supply. Brass was one of the few materials readily available, so it was used especially often in the 1940s and early 1950s. Skilled designers cleverly turned these material shortages into an advantage.

Paavo Tynell (1890–1973) was Finland’s first designer to specialize in lighting design. As the country was just getting electrified, Tynell preferred ornamental chandeliers and sleek functionalist fixtures. In the 1940s and 1950s he introduced designs marked by small perforations in the shades, unique floral details, and romantic leaf motifs. His most famous piece might be the Snowflake, which won over both Finnish and American buyers.

The most impressive Tynell pieces can sell for hundreds of thousands of euros at auction.

The 1950s sparked a boom

As wartime shortages began to lift in 1950s Finland, designers enjoyed a wider range of materials. Lamps were made of glass, copper, iron, aluminum, hardwood, silk, linen, and Perspex, an early term for acrylic plastic.

“What was best about the 1950s, from a designer’s standpoint, was the almost limitless freedom. Nearly every proposal got approved, and the selection of materials and colors was extraordinarily vast,” recalled designer Lisa Johansson-Pape (1907–1989) in a 1985 interview.

Designers had even more freedom at craft-focused factories that could produce unique pieces and special runs alongside mass-produced items. It was typical for factory designers to create custom lamps for each new hospital, restaurant, or church.

These fixtures have a warm, modern look, designed with everyday needs in mind. Their streamlined silhouettes are often softened by delicate handcrafted details. After the shortages, there wasn’t much demand for bold experimentation.

Three notable companies

In the early 1950s, three companies led the way in light fixture production: Orno, owned by the Stockmann department store; Idman, which specialized in mass production; and Taito, celebrated for its beautiful details (although it merged into Idman in the mid-1950s due to financial troubles).

A small but highly skilled team handled the design work at these successful companies.

At Stockmann-Orno’s design office, two younger designers were at work. The head of lighting design, Lisa Johansson-Pape, specialized in metal, glass, and fabric fixtures, while her colleague, the minimalist Yki Nummi (1925–1984), focused on plastic fixtures. Together, they guided lighting design in a more streamlined direction.

Aalto worked on classics

In the 1950s and 1960s, new designers and manufacturers entered the scene, most notably the legendary Finnish architect Alvar Aalto (1898–1976). Aalto created his first lighting models for his buildings back in the 1920s, though they were produced only as one-offs at that time. In the 1950s, as Aalto’s office worked on major public projects—such as the headquarters of Finland’s Social Insurance Institution and the Säynätsalo Town Hall—numerous new lighting designs were developed for those interiors, many of which later became classics.

When Viljo Hirvonen took the helm at Valaistustyö Ky and began series production in 1953, Aalto’s fixtures became available to home decorators, too. Some are still in manufacturer Artek’s collection.

Beyond Alvar Aalto, many designers dabbled in lighting design during the 1950s, though mostly on the side. Ilmari Tapiovaara (1914–1999) created the lattice-like Maija Mehiläinen lamp collection, while Tapio Wirkkala (1915–1985) designed angular Wir bulbs for Airam, as well as glass and metal fixtures for Idman.

Toward the end of the decade, Antti Nurmesniemi (1927–2003) created plastic-strip lamps that hinted at a new era for Vuokko Oy. Other notable 1950s lighting designers included Orno’s Svea Winkler and Klaus Michalik, as well as Idman’s Mauri Almari and Maria Lindeman.

Imitations became more common

In the 1950s, new businesses also emerged in the lighting sector. One of the biggest was Helsinki-based Itsu, which produced “Tynell-inspired” brass, metal, and glass fixtures at its and sold them in its Bulevardi location. Other newcomers in the 1950s included Valinte (later Lampukas), Lival, Metallivalmiste, Arisuo (Aris), and the multi-industry firm Pohjoismainen Sähkö.

These new factories often offered large product lines. Toward the end of the 1950s, for example, Itsu released a roughly 100-page lighting catalog. It seems they didn’t use professional designers, but instead adapted the most popular Finnish or Nordic designs of the time—some nearly identical to their originals.

The 1960s introduced plastic

The lighting market shifted at the start of the 1960s. Finland joined EFTA in 1961, removing protective tariffs and allowing low-cost imported fixtures to flood in. Domestic manufacturers had to decide more carefully what was worth producing. They cut their product ranges and improved efficiency. Traditional materials like brass and glass gave way to newer, more affordable, and easier-to-work materials. Brass was replaced by painted sheet metal or aluminum, while glass was replaced by plastic.

Plastic enabled entirely new shapes. Early examples include Yki Nummi’s Modern Art (1955), which combined two types of plastic, and the acrylic Lokki (nicknamed the Flying Saucer) developed at the decade’s end. These lamps captured an emerging space-age spirit.

Interior design was also pushing the envelope, with households embracing bold colors and big patterns. Lighting followed suit. Plush plastic lamps and smaller metal fixtures lit up rooms in orange, yellow, red, and green. Plastic’s light weight and ease of shaping meant lamps could grow in size. A great example of the era’s style is Heikki Turunen’s mushroom-like La Boheme table lamp from 1969.

Fluorescent lamps overshadowed design

A technical innovation, the fluorescent tube, also changed the lighting scene, becoming common in public spaces during the 1950s and 1960s. There was less demand for the refined ceiling, wall, and spot lighting of earlier decades, since fluorescent tubes offered cost-effective illumination. Although lighting quality may have improved, atmosphere often took a hit.

Many home-lighting manufacturers, struggling financially, added imports to their selections. Veteran lighting designer Yki Nummi voiced his frustration: “... countless inferior items have been forced in, including Japanese paper lanterns, French wicker baskets, Central European crystals, and other odd gadgets. People seriously claim these parodies of real lamps create ‘illumination’.”

Vintage lamps are highly valued

The 1950s and 1960s were a remarkable time for Finnish lighting, which brought together real materials, refined details, and expert design. The subsequent decades proved tough for domestic industries, and many factories shut down.

Today, 1950s and 1960s lamps are in high demand on the vintage market, and even pieces that were once inexpensive are growing in value. With Tynell prices soaring, many enthusiasts are turning to brands like Itsu.