Shy, delicate, absentminded, and among Finland’s greatest—Rut Bryk turned clay into art

Rut Bryk was a contemporary visual artist, among the greatest. Ceramics was her signature material throughout her career, which lasted over 50 years. She shaped pieces of clay into brilliant visual worlds at ceramics company Arabia’s art department.

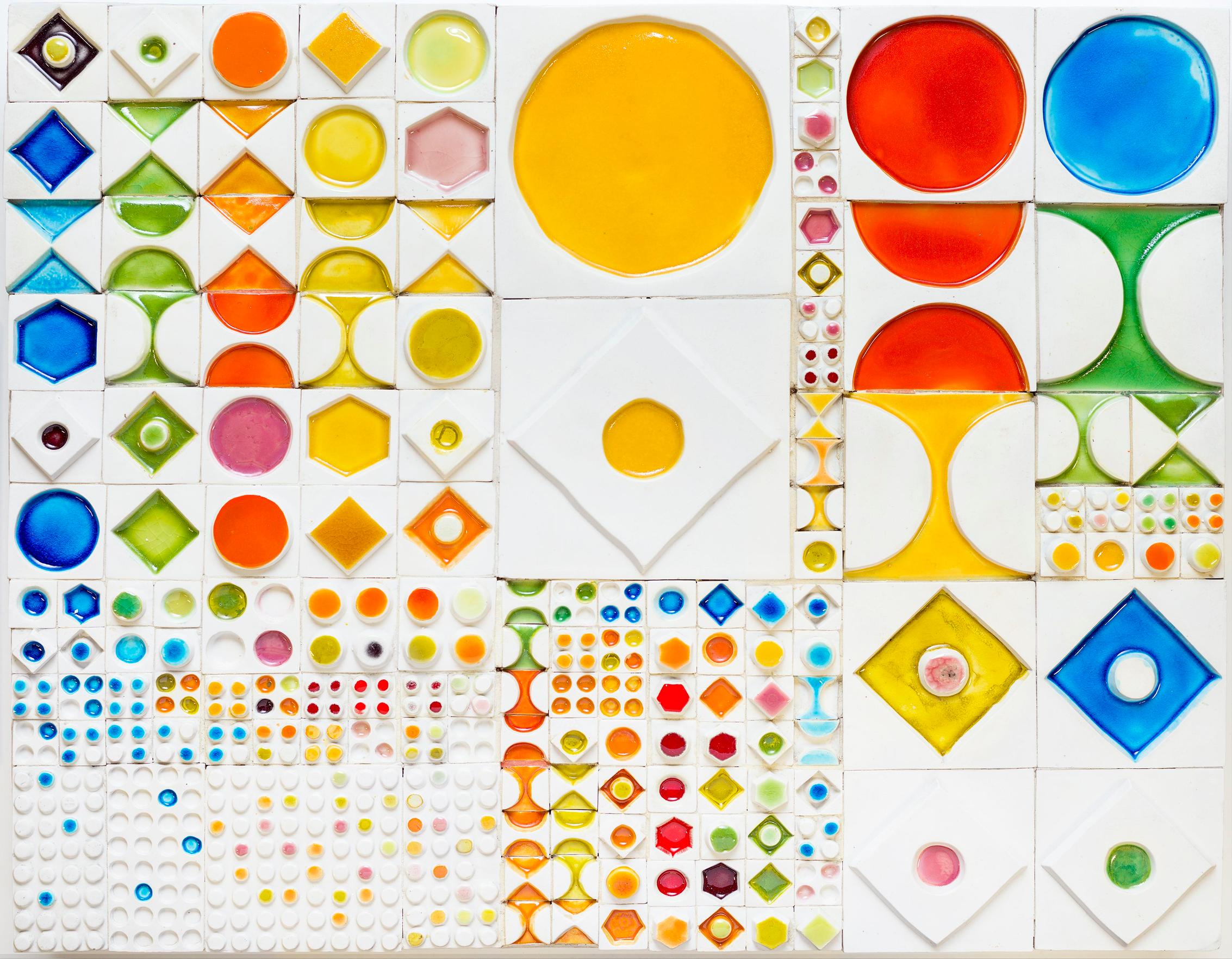

I still remember the moment I fell in love with Rut Bryk’s art. One sunny afternoon, I stepped into the lobby of Helsinki City Hall, where I was transfixed by an almost entirely white piece composed of small ceramic fragments called City in the Sun (1975). I felt something similar to what the French writer Stendhal experienced in Florence in the early 19th century: a rush of beauty made his heart race, leaving him dizzy and faint. He was completely enthralled by what he saw, and so was I.

City in the Sun is from the white period of Rut Bryk’s art which started in the late 1960s and continued to the early 1970s. She revisited this period in her final major piece, the Ice Flow relief (1987–1991), for the entrance hall of the President's official residence.

Linnea Rut Bryk was born in Stockholm on October 18, 1916, as the third child in a cosmopolitan family. Her Austrian father Felix Bryk studied art in Florence, where he met the Finn Aino Mäkinen. Aino had traveled there with her sister Maija and her sister’s husband, painter Pekka Halonen. Felix and Aino were married in Copenhagen, and they made their home in Stockholm.

Linnea Rut spent summers in her grandmother’s house with her mother and siblings. The surrounding landscapes of Karelia became her spiritual home, which later appeared in the moods and themes of her work.

After her parents’ marriage ended in divorce, Aino Bryk moved to Helsinki with her children. Known as Linnea throughout her childhood, she began using her other given name, Rut, in her twenties. This was her way of breaking from the family and stepping into adulthood. Her father had admired the biologist Carl von Linné and thus gave his daughter the name Linnea.

Initially, Rut Bryk wanted to become an architect. She was delicate, shy, and often late, so her older brothers—both studying engineering—persuaded her not to pursue what was seen as a masculine profession. Instead, Bryk took up graphic design at Ateneum.

Inspired by an ”infinitely wonderful” colleague

When she graduated in 1939, the school’s principal Arttu Brummer helped her find a job illustrating and designing textile patterns. Her remarkable career took off in 1942, when Kurt Ekholm, head of the Arabia art department, saw Bryk’s work at an exhibition and invited her to join as a trainee.

“I had never worked with ceramics before. I hadn’t even touched clay since childhood, when I ran barefoot through puddles in Karelia,” Bryk wrote in her diary. Nonetheless, she had admired Arabia’s artists and imagined the ninth-floor art department as a magical place.

And to her, it became exactly that. Within those walls, Bryk created her most enchanting pieces and led the way in modern Finnish and international ceramic art. She was not just a ceramic artist but also a contemporary visual artist who worked primarily with clay—for more than fifty years.

Her first mentor at Arabia’s art department was her colleague Birger Kaipiainen, a sensitive artist who became both an inspiring example and a close friend. Bryk said it was the “infinitely wonderful” Kaipiainen who taught her the technique, which she used in her first painterly ceramic tiles. Before long, Bryk developed a tile-based method that best fit her personal form and color language.

Works transform and evolve

Bryk often built large compositions from small elements. Over time, her art became increasingly three-dimensional. This shift is most visible in her architectural motifs, which evolved from buildings depicted on tiles to abstract reliefs assembled with mathematical precision.

Themes that were of personal important to Bryk—women, children, plants, flowers, and birds—gradually disappeared from her works.

She also went through a major change in color. Her somewhat dark, hazy hues of the 1940s gave way to bright, playful colors in the 1960s, followed by black-and-white postmodern scenes, and finally an almost pure white that captured subtle shifts of light and shadow.

Bryk spent her entire career at Arabia’s art department but never designed ceramics for mass production.

Instead, she created everyday textiles for an export collection from 1960 to 1963. The Seita collection, woven with patterned designs, included both interior and clothing fabrics, as well as finished products. According to Greta Muur, who studied the series, Bryk created most of it at a farm near lake Inari. The place was especially significant to her and even more so to her husband Tapio Wirkkala.

Her marriage lasts over 40 years

Her marriage to designer Tapio Wirkkala began in 1945 and lasted until his death in 1985. Birger Kaipiainen introduced them to each other, and soon after their first meeting, Tapio and Rut were inseparable. They had two children: interior architect Sami Wirkkala and the visual artist Maaria Wirkkala.

Through many conversations, the couple influenced each other’s perspectives, which in turn shaped their work. They only worked on a few projects together, but the results were remarkable. A great example is the delicate Winterreise porcelain set Tapio Wirkkala designed for porcelain manufacturer Rosenthal. Rut decorated the set with a wintry motif.

If anyone asked what Bryk intended to express in a particular work, she usually stayed silent. She wanted people to interpret her art in their own way, informed by their own background.

The Tapio Wirkkala Rut Bryk Foundation’s collection is held at EMMA – Espoo Museum of Modern Art. Its visible storage lets visitors explore Bryk’s work in depth. The area combines storage, exhibition space, and museum staff workstations, with around 2,500 objects on view. The rest are in crates and on pallet racks in the same space. The visible storage is open permanently alongside the museum’s other exhibitions.