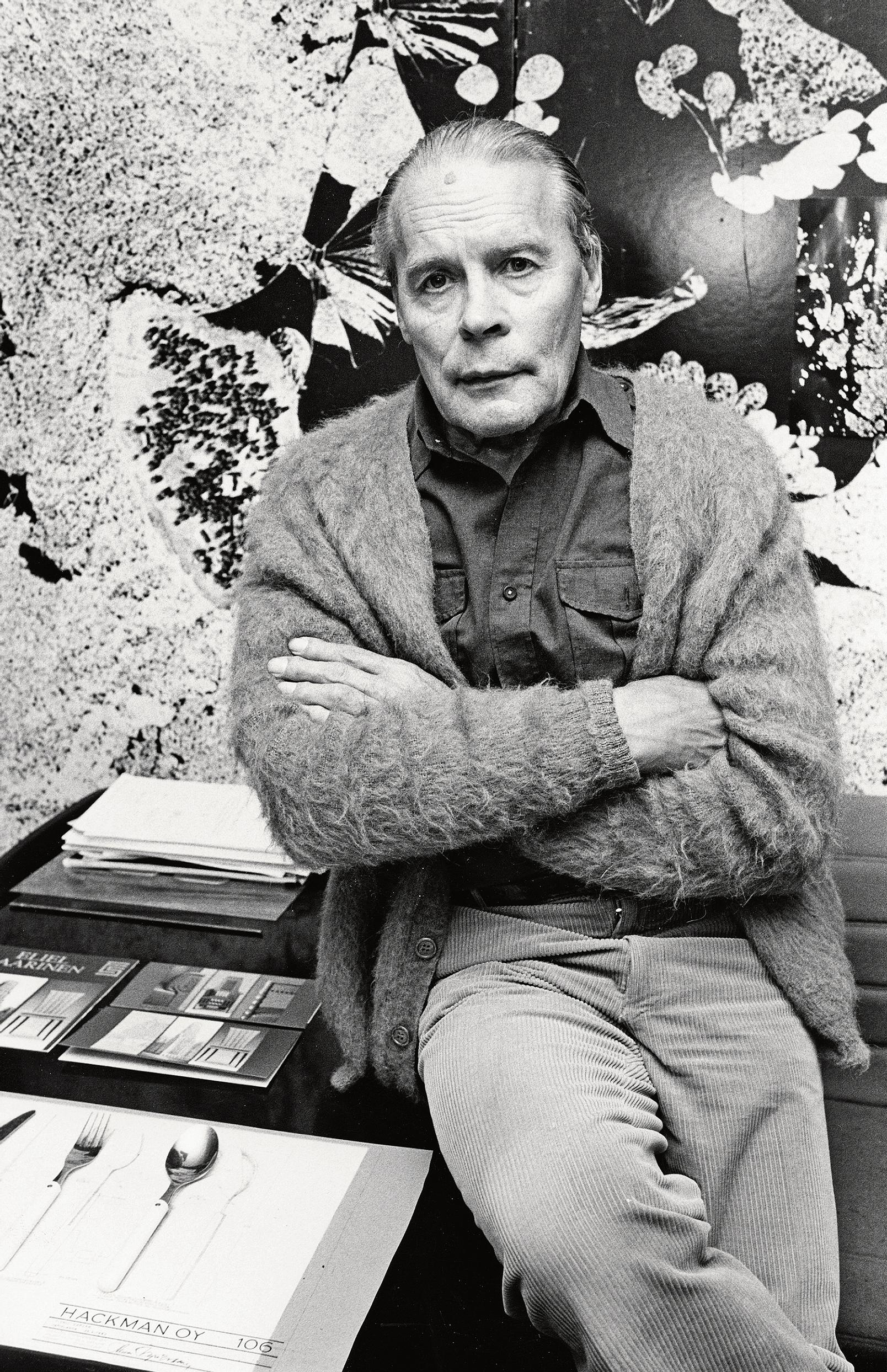

Renowned Finnish designer Ilmari Tapiovaara rejected unnecessary gimmicks—the purpose of furniture had to be clear at first glance

Ilmari Tapiovaara (1914–1999) designed sleek, versatile furniture for everyday use. He is especially known for his Fanett and Domus chairs, but his extensive body of work also includes tables, lamps, textiles, and household items.

Ilmari Tapiovaara was born into a forester’s family in 1914. His childhood home had a strong appreciation for culture, and many of his brothers were artistically gifted. Tapio became a visual artist and graphic designer, Nyrki a film director. Ilmari himself was a talented draftsman. In his twenties, he was admitted to Taideteollisuuskeskuskoulu (“Central School of Applied Arts”, now Aalto University School of Arts, Design and Architecture) and felt he had found his place.

In the 1930s, Finnish design and architecture were undergoing revolutionary changes. During his school years, Tapiovaara embraced the idea that industrial mass production and good design should serve all social classes.

The furniture factory Asko-Avonius hired the 25-year-old Ilmari Tapiovaara as its artistic director just before the Russo-Finnish War of 1939–40. He designed a collection of ten pieces of furniture for the 1939 Housing Exhibition. The new collection was on display for only seven days before the war broke out. The furniture never went into production, and the batch of fifty prototypes that had been ready was destroyed in the bombings.

During the trench warfare period, Tapiovaara served as the head of the production office of the 5th Division in the forests of East Karelia. Various army construction and interior solutions were created under his guidance: bunkers, canteens, cowsheds, utensils, and furniture. Tools were scarce, and wood was sourced from the surrounding forest. Later, Tapiovaara considered this time as the best higher education of his life.

After the war, Tapiovaara decided not return to Asko’s employment. The collaboration continued later when he designed many iconic pieces of furniture for Asko in the 1950s.

Although materials were rationed in a country recovering from the war, furniture was needed for homes, schools, and kindergartens. His wife, interior architect Annikki Tapiovaara assisted him in design work. She brainstormed with her husband and helped finalize the design drawings. In the early 1950s, they established their own design office. In 1967, their son Timo Tapiovaara, who was studying to become an interior architect, also joined the team.

The couple achieved their long-awaited breakthrough when they won the competition to furnish the student dormitory Domus Academica. The Domus chair, designed in 1946, reflected the scarcity of the wartime era: solid wood, two pieces of plywood, and a few screws combined into an excellent design. Despite its simple structure, the seat is ergonomic. For a long time, this modern chair was mainly used in public spaces, as it was initially considered too austere for homes. Stackable and easy to assemble, the Domus was suitable for mass production, and transporting it was inexpensive. After the wars, the chair became an important export product.

Although Ilmari Tapiovaara created a wide variety of designs during his career, he kept returning time and again to designing chairs. The story of his spindle-back chairs began with the Fanett in 1949. Production started at the Swedish Edsby factory in 1949 when the company wanted to utilize surplus material from wooden ski manufacturing. From 1955 onwards, the chair was also available in Finland when Asko began producing it.

Fanett was a sales success in the 1950s and ’60s. In Sweden alone, over five million chairs were produced. Its popularity inspired other furniture factories to develop their own or slightly modified spindle-back chair models. Even Asko produced the chair under another name during its final years of production. The genuine Fanett chair can be recognized by the hollow in its seat and the curved front edge.

At first, spindle-back chairs were widely used as kitchen dining chairs, but they later became more common in other rooms as well. Based on the Fanett, Tapiovaara later created the high-back Mademoiselle (1957), the rounder Crinolette lounge chair (1961), and the Mamselli rocking chair (1960).

Tapiovaara’s designs reflect an appreciation for peasant culture and craftsmanship traditions. His popular chairs are adaptations of the English spindle-back chair, which had furnished Finnish farmhouses for centuries. Among Tapiovaara’s best-known works is also a modern version of the farmhouse furniture set, the Pirkka series (1955) with tables, chairs, and benches.

Ilmari Tapiovaara loved performing and speaking, and he was a popular lecturer in his time. Tapiovaara had become a brand, which made him a target of criticism. In the late 1960s, younger designers accused him of elitism, even though his design approach had been to create high-quality yet affordable furniture.

In the early 1980s, Tapiovaara fell ill with Parkinson’s disease. When he could no longer draw, he decided to close his office in 1984. As the disease progressed, his career fell into oblivion. For a couple of decades, Tapiovaara was a forgotten master in Finland, but there was interest elsewhere. He died in January 1999 and did not live to see how online shopping became widespread and, as part of the vintage boom, the furniture he had designed began to sell briskly again. Something is different to the 1950s, however: the price tag on the chairs. Today, Artek’s selection features nearly twenty pieces of furniture designed by Tapiovaara.

Sources: Elina Jaakkola’s article “Ilmari Tapiovaara” in Avotakka 4/2013 and Antti Järvi’s article “Fame and Oblivion” in Avotakka 6/2014.