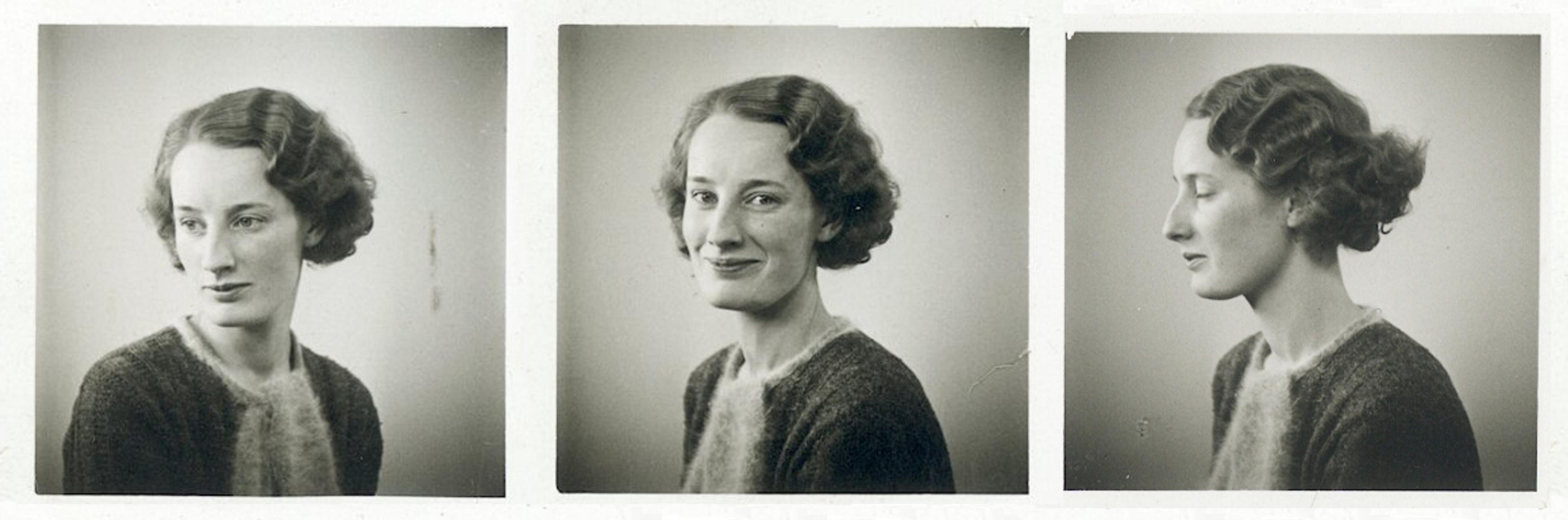

Gunnel Nyman’s prolific career cut short at just 39—“As a glass artist, Gunnel Nyman was a poet”

Gunnel Nyman laid the foundation for the modern glass design in Finland. But who was she really, and what kind of life did she lead?

Gunnel Nyman was the first modern glass artist in Finland. She embodied the spirit of her time—the 1940s post-war reconstruction—in glass and paved the way for the next top designers of the following decade.

Most people know Nyman either by name or through her classic works, such as Serpentiini “Serpentine”), Calla, Helminauha “String of Pearls”), or her popular spiked-mold vases and glasses.

It is often overlooked that Gunnel Anita Gustafsson, born in Turku, Finland, in 1909, initially trained as a furniture designer at the School of Art and Design. After completing her studies in 1928–1932, she designed furniture for Boman, lamps for lighting companies Taito and Idman, and fairly early on, glass for the Riihimäki, Karhula, Iittala, and Nuutajärvi glass factories. At that time in Finland, it was not possible to graduate as a glass artist, and it was common for artists to design products for different factories and from various materials.

Even more often, Gunnel Nyman herself seems to fade into the background of her works and their brilliant legacy. Her thoughts on the genesis and making of her works have also been nearly forgotten. This aspect of the favorite of collectors and auction houses remains little known.

Gunnel Nyman’s exceptional design talents were recognized early on, and she began receiving awards from 1930 onward. At the Paris International Exposition in 1937, Nyman received a gold medal for her works for Riihimäen Lasi and two silver medals for her furniture and lamps for Boman and Taito. At the Milan Triennial, she earned a bronze medal in 1933 and a posthumous gold medal in 1951.

Most of her works were utility glassware, as her sculptural art glass predominantly went to foreign exhibitions and private collections.

Mass-produced art glass began to emerge at Nuutajärvi glass factory in the late 1940s.

So, Gunnel Nyman was extremely prolific. Yet she made time for family life, which was very important to her—perhaps even her everything.

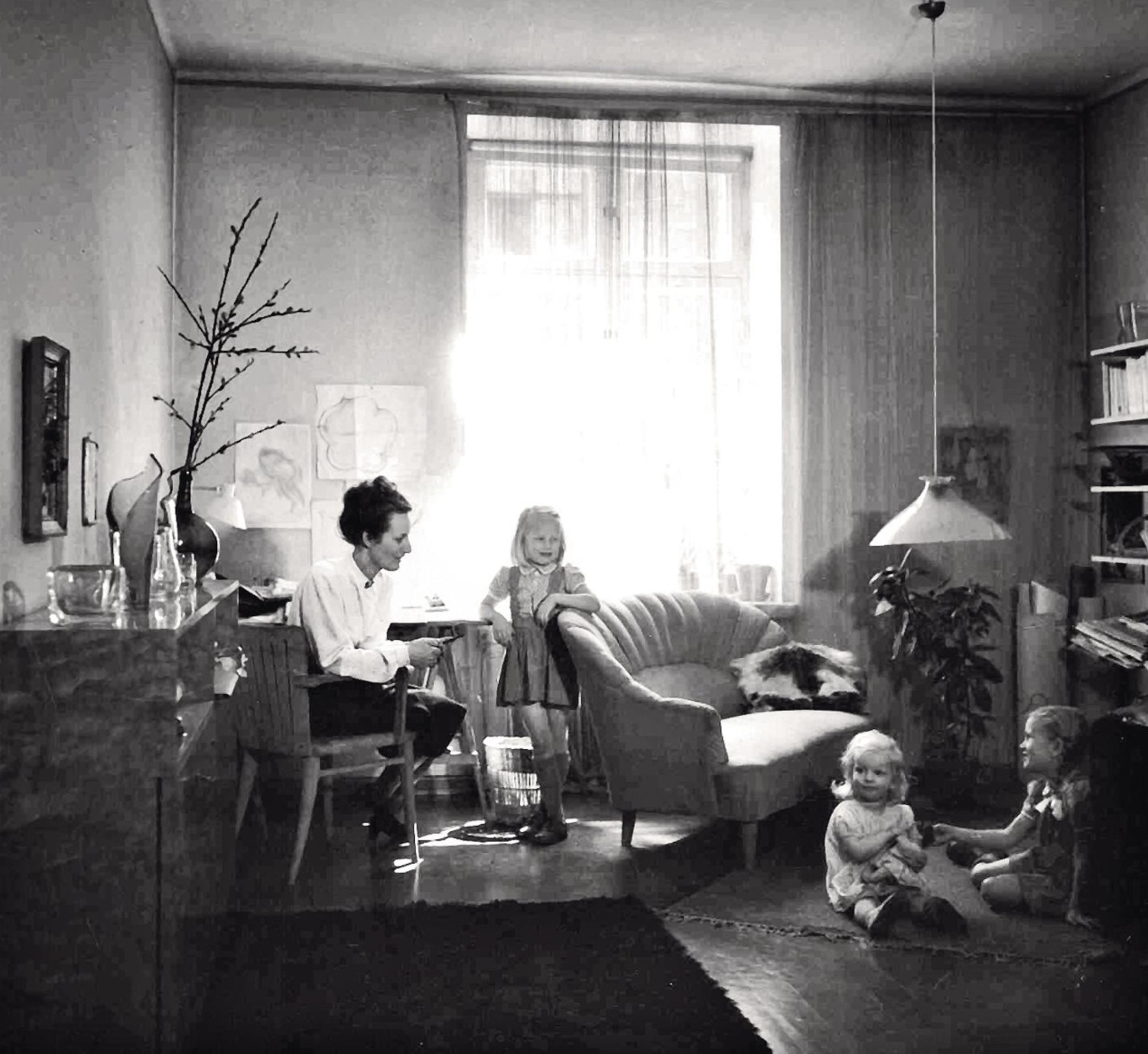

In 1936, Nyman married senior lawyer Gunnar Nyman, and the couple had three daughters: Anneli, Inge, and Lena. The family lived in central Helsinki, and Gunnel cared for her children at home, where she also worked after the children went to bed.

She would sketch late into the night. Typical for a female artist in an era of modest living, Nyman’s sketchbooks are densely filled. Different items often appear side by side on the same page—and sometimes also shopping lists and notes to playground supervisors.

Rather than working in a spacious studio, Gunnel Nyman chose to work at home with her children in a small space. In the evenings, her husband might also work from home, allowing the family to live tightly together.

By all accounts, Gunnel Nyman was a cheerful, curious, cultured, wise, inspiring, and hard-working person who was genuinely humble. She was not proud of herself but took unreserved joy in her glass works and the beauty crystallized within them. Everyone liked Nyman—children, colleagues, and glassblowers alike.

At the Nuutajärvi factory, her colleagues always eagerly awaited the artist’s arrival, and Nyman herself was equally enthusiastic about getting into the glassblowing studio, dressed in overalls and rubber boots, with a scarf tied around her head.

Once, she invited the factory manager’s little daughter to join her in drawing. At the time, the Helminauha vase was still in its sketch form. Gunnel explained her creation to the child: “Look how beautifully the pearl necklace rests in the glass, just like on a woman’s neck.” That child later became an art historian.

Gunnel Nyman had a special connection to her favorite material. To her, beauty was about the harmoniously planned combination of substance, form, proportions, and decorations, in which the material is clearly the dominant factor. The material had to be so dominant that one couldn’t imagine the object being made from any other substance.

The secret of this vision lies in the line formed by drawing. Nyman was interested in the specific moment in glassmaking when the molten glass solidifies and light creates different spaces and reflections in the glass, and above all, the silhouette of the object.

While working in the studio with the glassblowers, she was also inspired by mistakes. The smoke technique used when making art glass items was born when smoke accidentally entered the piece and colored it during one glass blowing session.

Nyman’s friend Dora Jung said: “As a glass artist, Gunnel Nyman was a poet.”

Nature was perhaps Gunnel Nyman's most important teacher after all, and she did consider the forms of nature to be perfect. Nyman's own favorite piece was Fasetti I from 1941. It's a very simple art object—an oval piece of freely blown clear crystal with a polished edge. In Nyman's archive, there's a fine sketch showing a leaf being simplified and becoming increasingly abstract. What remains is only the essence of nature. Fasetti I looks as if it flew in through the window and settled on the table.

Fasetti is also one of the art objects that ultimately brought Gunnel Nyman to the awareness of the wider world. This happened at Stockholm’s Liljevalchs Art Gallery in 1946, at an exhibition displaying pieces from the Finnish art and design industry. Thanks to its great success, the exhibition came to Finland the following year and was held at the Artek furniture company.

Textile artist Dora Jung also participated in the same exhibition. She and Nyman were close friends and held several joint exhibitions both in Finland and abroad. Media company Bonnier’s monthly magazine wrote in 1948 about the duo’s exhibition in Gothenburg: “I only wish to give compliments to the artists, Dora Jung and Gunnel Nyman, who have given us the very best that Finland has to offer in the fields of textiles and glass.”

Gunnel Nyman tragically fell ill with cancer and passed away at only 39 years old in 1948. She spent her last summer with her family in the outer archipelago of southern Finland. When their mother died, the family’s youngest daughter was only three years old.

That summer, Dora Jung visited the island. She wrote a beautiful poem about her visit and made a drawing of the family’s three children playing by the sea. In turn, Gunnel’s husband, Gunnar Nyman, wrote about his wife: “Illness crushed her future plans, but she bore her sickness with incredible spirit and without bitterness. She was grateful for the life she was able to live and the work she was able to do. She was a person who created a whole from the different parts of her life.”

Although Gunnel Nyman’s nearly 20-year career was unique, she truly blossomed during her last two years of life. Even when seriously ill, the artist reached a stage where her works were almost spiritual.

Her last new work at Nuutajärvi was Ruusunlehti (“Rose Petal”). It is freely blown glass with a clear interior, a pink underside, and an edge polished flat.

Ruusunlehti appears to float, rather than sit on the surface.

Dora Jung describes the artist like so: “Gunnel Nyman’s glass speaks of her as a person, of impulsive imagination and warm humanity, of enthusiasm and humility toward the material, of a happy, harmonious person who sought beauty and fully surrendered to joy and gratitude wherever she encountered them—in items, nature, and life. Joy and contagious enthusiasm were her essence throughout her life.”

Gunnel Nyman made her art, herself, and her home into a harmonious and unique work of art.

Photos by the Nyman family archive and Bukowskis