Designer Timo Sarpaneva’s remarkable journey—12 glimpses into the life of the Finnish design legend

Designer Timo Sarpaneva (1926–2006) received his first lessons at the forge of his maternal grandfather, the village blacksmith Abel Hujanen, in Pielavesi, Finland. Over his decades-long career, he had countless surprising experiences and met many colorful personalities, from Andy Warhol to Urho Kekkonen. His spouse, Marjatta Sarpaneva, reveals it all in a biography.

Abiography by Timo Sarpaneva’s spouse, Marjatta Sarpaneva, called Timo Sarpaneva—taide ja elämä (“Timo Sarpaneva—art and life”) was published in fall 2020. We’ve gathered 12 fascinating and surprising facts about this design legend from the book.

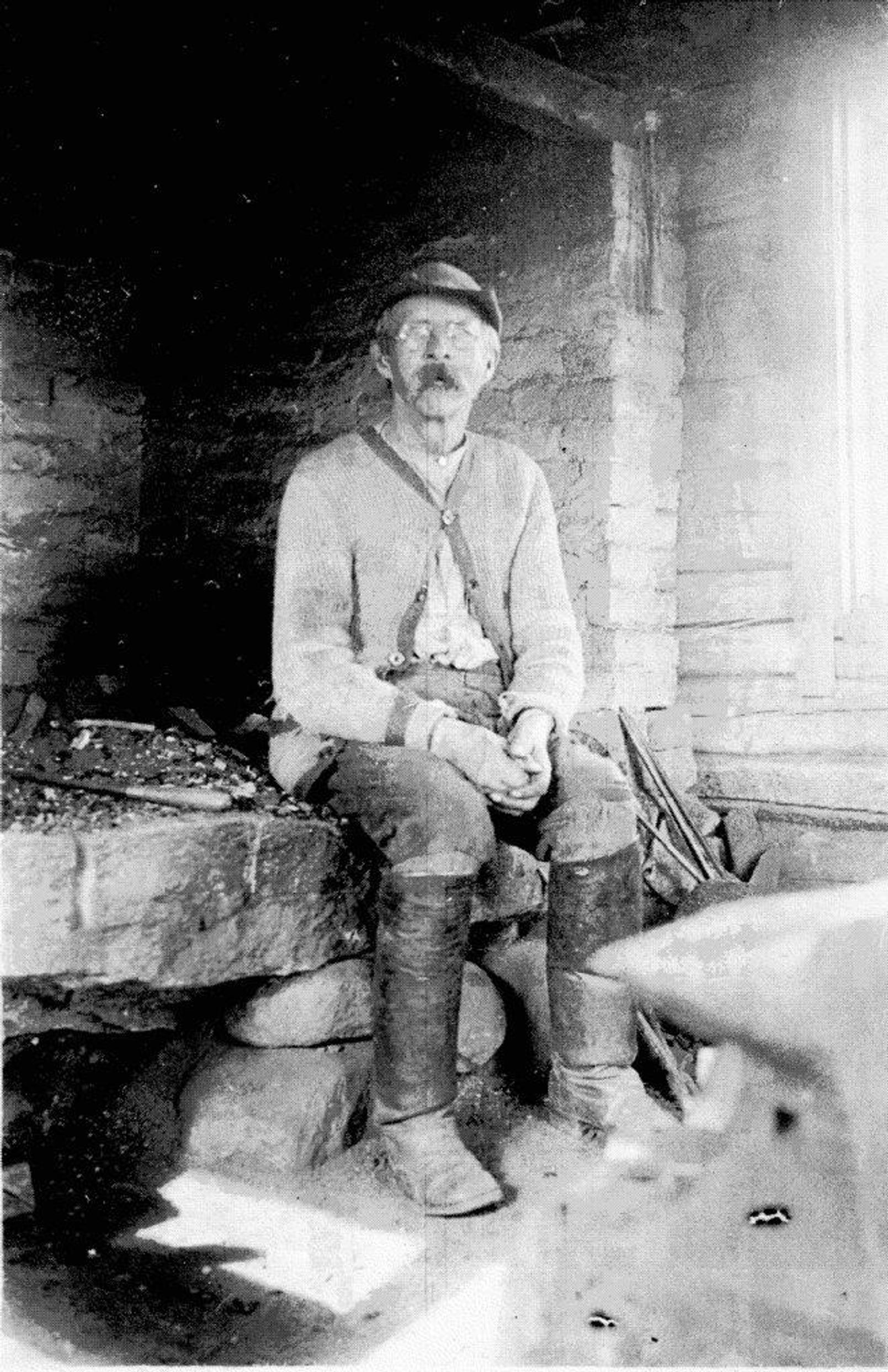

1. Sparks flew onto young Timo’s knees in the forge of the village blacksmith

Timo Sarpaneva’s maternal grandfather, Abel Hujanen, was the blacksmith in Säviäntaipale, Pielavesi. One day, he was forging a scythe blade on the anvil. Little Timo pumped the bellows and watched so intently that he didn’t notice the forge spitting sparks onto his bare knees.

2. A precious inheritance from his uncle

His father, Akseli Storm, disappeared early from Timo and his brothers’ lives. Alongside their mother, Martta, their cultured and unique uncle Tuure helped raise the boys. From him, Timo inherited the only valuable item the family owned: an ornate silver folding knife he had admired since childhood. It was the only material inheritance Timo ever received.

3. Volunteering for the army at 17

In April 1944, at the age of 17, Timo Sarpaneva volunteered for the Finnish army. He was swiftly trained as a light mortar forward observer and loaded onto a truck bound for the Karelian Isthmus, where the defensive lines had collapsed. In the end, the truck stopped in the yard of the Nummenkylä women’s prison after radio broadcasts announced a ceasefire on September 4, 1944. Afterward, Sarpaneva returned to Ateneum, or Taideteollinen keskuskoulu (the Central School of Art and Design), where he had been accepted back in 1940 at the age of 14.

Sarpaneva paid for his studies by working on log drives in North Karelia, eventually becoming the crew foreman.

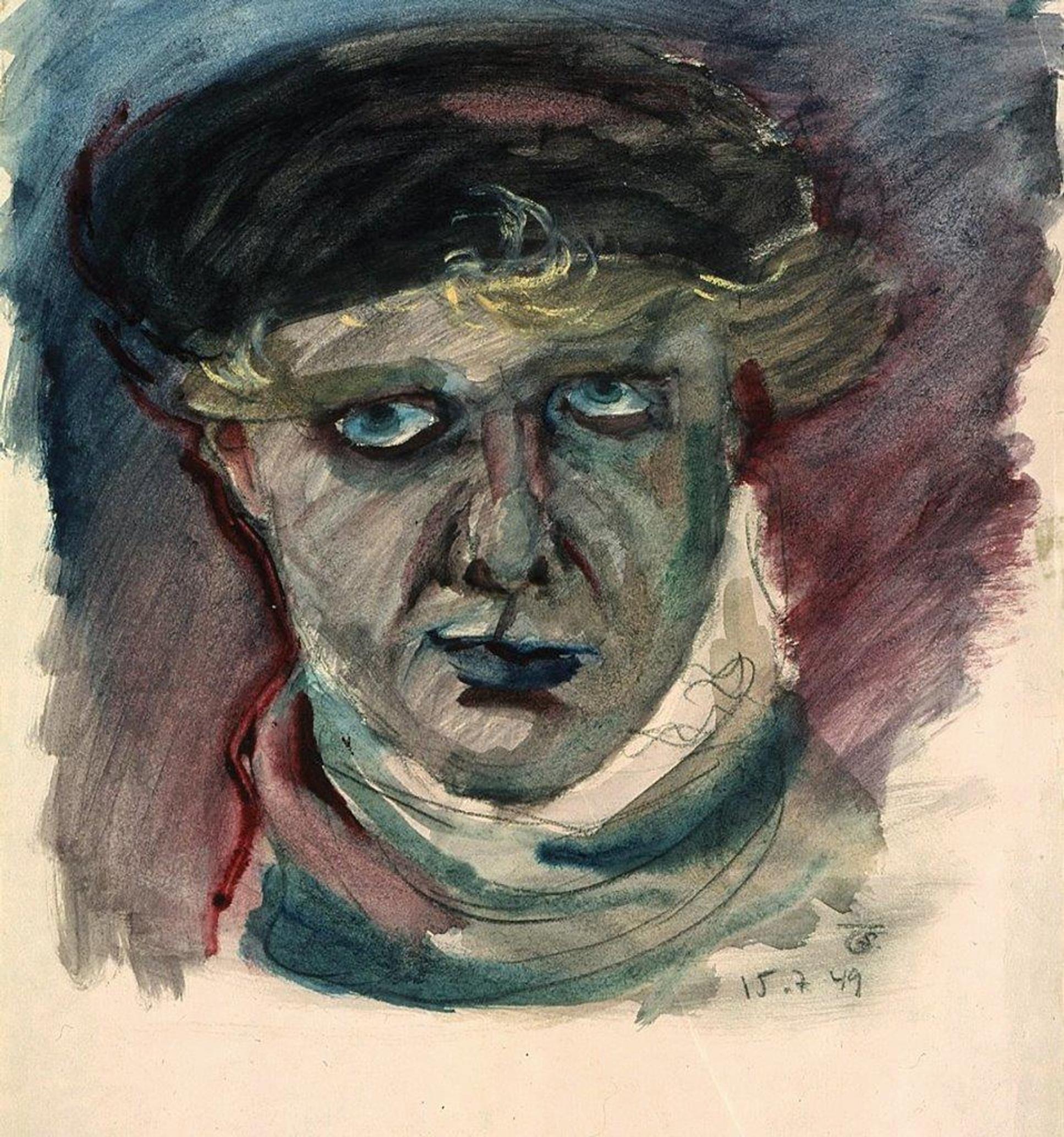

4. Working as a successful lumberjack to fund his studies

From 1946 to 1949, Sarpaneva paid for his studies by working on log drives in North Karelia. The work was tough—balancing on slippery logs from morning till evening and breaking up jams in calmer waters. Eventually, Timo was promoted to the crew foreman.

5. The poor artist stood his ground

In 1949, Timo Sarpaneva took second prize in a Nordic glass design contest held by Riihimäen Lasi (Riihimäki Glass), earning him an invitation to meet industrial counsellor Roope Kolehmainen. He offered Sarpaneva a designer position at the glass factory, and Sarpaneva cautiously inquired about the salary. The counsellor gave him a cold look from behind his desk, and said there’d be no pay—instead, they would make him famous.

That ended the discussion. Poor and hungry, the aspiring artist gathered up his portfolio, buttoned his coat, and walked out. Outside, the black car and driver were gone. A heavy downpour beat against the muddy road as the dispirited artist headed for the train station.

6. Not a single glass went to waste

In 1955, Sarpaneva began designing mouth-blown everyday glassware for the Karhula-Iittala glass factory, which led to the i-glass series. Together with the factory chemist Keijo Laitinen, he developed a new color palette: purple, blue, and green tinted with gray, which also appeared by itself in the glassware. During the 1956 general strike, the glassblowers were off, but management was allowed to do glass experiments as long as the pieces were destroyed. “But I never smashed a single piece—there would have been hundreds,” Timo later recalled.

Sarpaneva liked to collect islands that no one else wanted or appreciated.

7. Island shopping in the middle of the night

Timo Sarpaneva liked to collect islands that no one else wanted or appreciated. In 1955, on a summer night in Iniö, he purchased his first island. He, writer Henrik Tikkanen and fisherman Erik Koskinen had been relaxing on a deserted rocky shore, with a bit of moonshine fueling their conversation. Erik encouraged Timo to buy the dark speck on the horizon, so he’d always have somewhere to return to in this place he’d come to love. A down payment of one hundred marks was required. They finally borrowed it from the local physician, whom they had to wake in the middle of the night.

8. A candleholder like no other

In 1966, Timo started designing glassware that would be used at Christmas lunches he shared with friends. His master glassblower at the Iittala factory, Reka Löflund, had an idea while looking at the finished glass stems. He thought they looked more like candleholders than drinking glass stems, and told Timo so.

Reka and his blowers worked overtime and produced about twenty good pieces that Timo intended as Christmas gifts for the board members of A. Ahlström Oy. In the spring, Timo returned to Iittala and said that such a fine product should be produced commercially. They eventually discovered a way for serial production. The Festivo candleholders have been in continuous production since 1967, with an estimated 15 million sold.

9. A money-making tip from Andy Warhol

In 1969, Sarpaneva met artist Andy Warhol at the opening of his Ambiente textile exhibition in New York. Warhol told him, “Listen, Timo, you’re being really dumb. Why do you call these textiles? They’re paintings. You should cut them up, frame them, and sell them as paintings—that’ll make you a millionaire.” Timo didn’t follow that advice—and never became a millionaire.

10. The president settled a family dispute

One summer day in 1976, the phone rang at Marjatta Sarpaneva’s home, and she answered in frustration. Her spouse, Timo, had been missing for days. “Is that Jatta? This is Urho… Urho Kekkonen. Timo has ended up here at Mäntyniemi, and Urho is asking that Jatta not be angry. You see, we men can be a little tricky sometimes.”

Remorseful and looking a bit worse for wear, Timo came home after the conciliatory phone call, bringing a small bouquet of forget-me-nots with him.

Sarpaneva slept on an emergency stretcher on the hot shop floor, fifteen minutes at a time. The nearly nonstop work lasted six weeks.

11. Non-stop work and catnaps on a stretcher

In 1983, Sarpaneva said that glass is a spatial material. He was intrigued by its unique optical qualities. While running a workshop at the Iittala factory, he practically lived there, sleeping just fifteen minutes at a time on a stretcher in the hot shop. The nearly non-stop work went on for six weeks, resulting in the Claritas collection—64 unique works of art.

These objects owe their magic to large air bubbles, an idea set in motion by glassblower Jouni Sinkkonen, who made a glass pendant enclosing air inside a clear bead. In 1997, Timo ended his contract with Iittala, because it had become impossible for him to continue working under their new conditions.

12. Venice opened dazzling horizons

In Murano, Venice, Timo discovered new possibilities and a slower-cooling glass mass. He joined maestro Pino Signoretto’s studio, developing new pieces and a collection of sculptures—some of the finest of his career. In spring 2000, Marjatta and Timo traveled to Venice for the last time. Timo seemed exhausted. At a vaporetto stop, he suddenly said, “Jatta, if it weren’t for you, I wouldn’t do anything anymore. Give me strength.” Something was seriously wrong.

Timo Sarpaneva’s life

- Timo Sarpaneva was born in Helsinki on October 31, 1926. He graduated as a graphic designer in 1948. As a graphic designer, he created Iittala’s iconic “i” logo. Originally, the logo was intended just for his own line of everyday glassware.

- The Danish glassworks Holmegaard once offered him a design position, but he ultimately took Iittala’s offer, which promised him free rein. His first work there was a small sculpture called Hammas ("tooth"). He worked for Iittala as a designer for nearly 50 years, from 1950 to 1999.

- Sarpaneva first took part in the Milan Triennial in 1951, where his coffee pot cozy earned a silver medal. The embroidery was lovingly done by his mother, Martta.

- By 1954, he had designed the glass pieces Lansetti, Orkidea, and Kajakki. In the early 2000s, Kajakki sold for nearly one hundred thousand euros a Sotheby’s auction.

- Sarpaneva started designing everyday glassware in the ’50s. His earlier output was gloriously sculptural, but it was mocked in postwar Finland. The “one-flower” Orkidea vase got its name when someone asked what it was used for. “Just put a single white orchid in it,” was the reply. The teasing stopped when Orkidea was awarded a Milan Triennial prize and named the year’s most beautiful object by House Beautiful.

- Some of his best-known functional designs include the Festivo candleholders, the Tsaikka glass series, and a cast-iron pot—all still in production. The legend has it the Festivo candleholders were originally designed as wine glasses.

- Sarpaneva was much more than a glass artist. He worked as a designer for international exhibitions alongside Tapio Wirkkala, as an industrial designer for steel, plastic, and porcelain items as well as clothing, and as a textile print design teacher at the School of Art and Design. He also served as the artistic director at Porin Puuvilla cotton factory and designed textiles for Tampella. In the 1960s, he designed Juniper menswear collections for Kestilä.

- Sarpaneva was married twice, collaborating professionally with both wives. As a final gesture of devotion, his second wife, Marjatta, designed his memorial on the Artists’ Hill at Helsinki’s Hietaniemi Cemetery.

- Timo Sarpaneva passed away on October 6, 2006, a few weeks shy of his eightieth birthday.