Ulla Procopé’s short but prolific career: how Valencia and Ruska continue to shine

Ulla Procopé’s heyday at Arabia lasted only about ten years, but in that time, she created several best-selling dinnerware series. Ruska, Valencia, and Kosmos have all made comebacks in recent years.

I received a brown, rustic-looking, partially glazed mug from a friend as a souvenir from America. It was purchased at a craft gallery in Washington and was said to be very trendy. I had a déjà vu moment: Ruska!

Ulla Procopé’s Ruska tableware, wildly popular in the 1970s and 80s, disappeared from view for decades. It wasn’t seen in trendy table-setting photos or on friends’ coffee tables. It stayed out of style for a long time.

Suddenly, Ruska’s time has come again. Vintage Ruska sets are now highly valued, and the Japanese in particular have been captivated by them. There’s a sense of earthiness—even rustic charm—in the air. Brown has also returned as a trend color in interior design.

Ruska pieces pair nicely with those softly glowing hues creeping into our taste: vintage rose, burgundy, forest green, warm orange-yellow, and smoky blue. Maybe I should have held on to my own Ruska collection instead of letting it slip from my cupboards to flea markets.

When Ulla Procopé (1921–68) designed the Ruska series for Arabia, she focused above all on usability. Ruska incorporated a new type of solid, durable glaze that was especially well suited to stoneware. Its base shape was her S-series.

Ruska became one of the ceramics factory’s most popular and long-lasting lines. Buoyed by its success, parallel versions were developed: the lushly floral Anemone and the much more graphic Kosmos, which hit the market in 1963.

The Kosmos series was produced in both greenish and blue versions, featuring simple linear motifs created by Gunvor Olin-Grönqvist—one of Arabia’s long-time designers.

This glazed series consisted of about 25 different pieces: plates, bowls, cooking and serving dishes, teapots, butter dishes, sugar bowls, and coffee and tea cups.

Production of the series ceased in 1976, while Ruska continued uninterrupted into the 1990s. The sturdy shape and colors of Kosmos make it timely—even aside from its high-quality ceramic craftsmanship.

Even before Ruska, Procopé designed the Liekki casserole series, for which Arabia’s lab developed a new mass that could withstand both oven heat and open flame. The immediate popularity of this everyday cookware was due to the fact that you could take the dish from the oven straight to the table, seamlessly fitting it into the place setting. Practicality and simplicity marked the spirit of the era.

Read more: Gunvor Olin-Grönqvist’s work remains on collectors’ wish lists year after year

Perhaps images of her youth in the French countryside also lingered in the designer’s mind. Officer father Alexander Procopé was sent as an observer to the Spanish Civil War, and the family lived in Perpignan in the French Pyrenees, near the Spanish border. Seventeen-year-old Ulla began her local studies at a convent school.

The rough, simple, and practical kitchen aesthetic of southern European rural culture undoubtedly left its mark on the young woman, who would later become a ceramic artist.

Upon returning to Finland, Ulla Procopé studied in the evening program at the Central School of Applied Arts, where the renowned teacher of composition, ornament, and freehand drawing Runar “Skåpe” Engblom picked her to become a full-time student in the day school.

Engblom was one of those sharp-eyed teachers who recognized each student’s distinctive talent. He was a furniture designer who later became a lecturer in the School of Applied Arts’ interior design department, but he directed Procopé—quite fortunately—toward ceramics.

As her body of work later demonstrated, Ulla Procopé mastered form, color harmony, and the secrets of rich surface decoration.

The other side of this functionalist was a thoroughly romantic spirit. You can glean this from the ND tableware she designed and its enchanting Valencia decoration.

The lush cobalt blue motifs have undoubtedly also been favorites of Arabia’s skillful porcelain painters. The joy of their craft practically radiates from the plates, cups, pitchers, and bowls, where each brushstroke reveals a delicate, expertly executed handmade touch. However, it’s said that painters needed time to shift from their formerly precise approach to the more spontaneous brushwork of Valencia.

Some of the Valencia line launched in 1961 stayed in production until 2002, when Arabia ended its hand-painted tableware series.

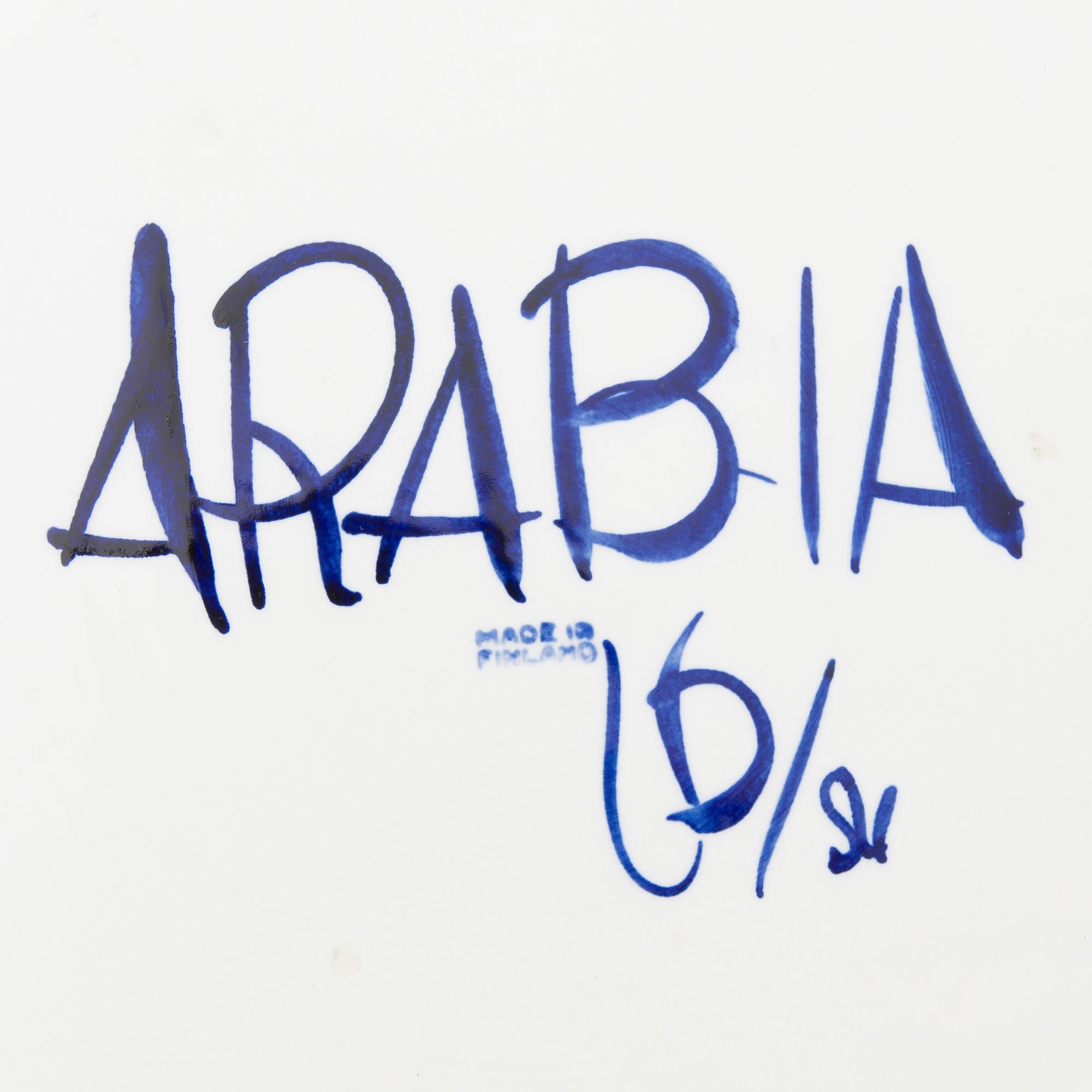

Even in the 1960s, porcelain painting was still taught in the evening program of the School of Applied Arts. Nowadays, when searching for these pieces, be sure to check the bottom: in addition to the designer’s initials, you’ll often find the porcelain painter’s signature.

Besides her hits—Ruska, Valencia, and Liekki—Procopé designed many other items over the years. However, she only got to create products that truly reflected her own vision and skills relatively late, at the end of the 1950s.

She began working at Arabia soon after completing her studies in 1948, first in the porcelain painting department under Olga Osol, known for her Myrna tableware. A few years later, she continued at the modeling and decoration department, then moved in 1956 to the product design department led by Kaj Franck. There, her colleagues were Kaarina Aho and Saara Hopea. Only then did Procopé’s talent and skills truly come into their own.

Ulla Procopé was born into an upper-class Finnish-Swedish family and received a suitable upbringing. Her mother Karin (née Spåre) passed away when the daughter was just three years old. Ulla’s baptismal name was royally impressive: Ulrika Eleanora Matilda.

Despite her background, Procopé preferred to keep a low profile and was happier among lab technicians, model-makers, and kiln operators at the factory than in the limelight or under studio lights.

As an artist, she was spontaneous, noting that she drew her best sketches in a headlong rush right before deadlines.

What else might have emerged had the artist’s career not been cut short by her death just shy of 50? The cause of her early passing was silicosis, also known as “stone dust lung,” a cruel occupational disease caused by decades of exposure to silica dust in the factory.

Even in the hospital, when the end was near, Procopé added to her ND series with a new, delightfully rustic, hand-painted decoration called Purpurijenkka.

Ulla Procopé died in the warmth of Tenerife, Spain, on December 21, 1968, only a little over a month after her 47th birthday.