“When I’m angry, I ground myself by knitting mittens”: three women want to change the world with crafts

For Kaarina, Marianne, and Laura, crafting is activism—a statement through which they aim to change society. The trio shows how knitting, embroidery, and mending can be more than just a calming pastime.

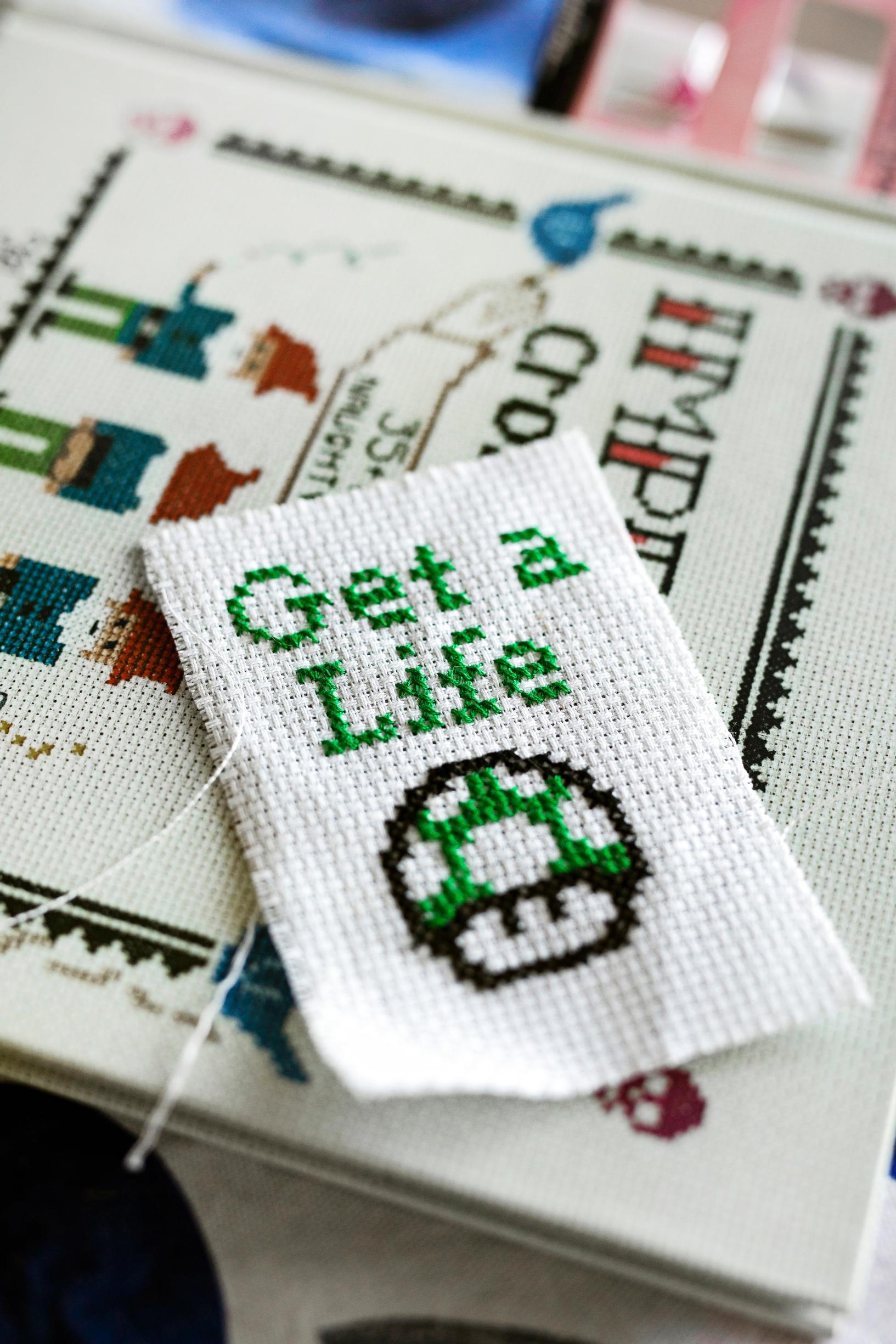

Marianne Savallampi, 38, Helsinki: “Societal anger is a recurring theme in my cross-stitch works”

I first heard about Radical Cross-Stitch about eight years ago. Back then, I was organizing queer feminist activities myself, such as graffiti workshops, gigs, and parties that highlighted the rights of sexual and gender minorities. My friends started organizing cross-stitch events, and I decided to give it a try. Now, I’ve been helping run the activities for about five years.

Radical Cross-Stitch is a feminist activism movement aimed at elevating the appreciation of craft as an art form and as a socially engaged activity. At the same time, it explores the different forms that feminist activism can take.

Anyone can start a Radical Cross-Stitch group, and such groups exist throughout Finland. In our meetings, everyone can work on their projects. In Helsinki, we strive to ensure that you don’t necessarily need your own tools. We’ve received yarns, fabrics, and needles as material donations. You don’t need prior cross-stitching skills; we share our knowledge with each other.

“Crafting is a gentle way to criticize. I’ve commented on issues like body norms and gender stereotypes through my works.”

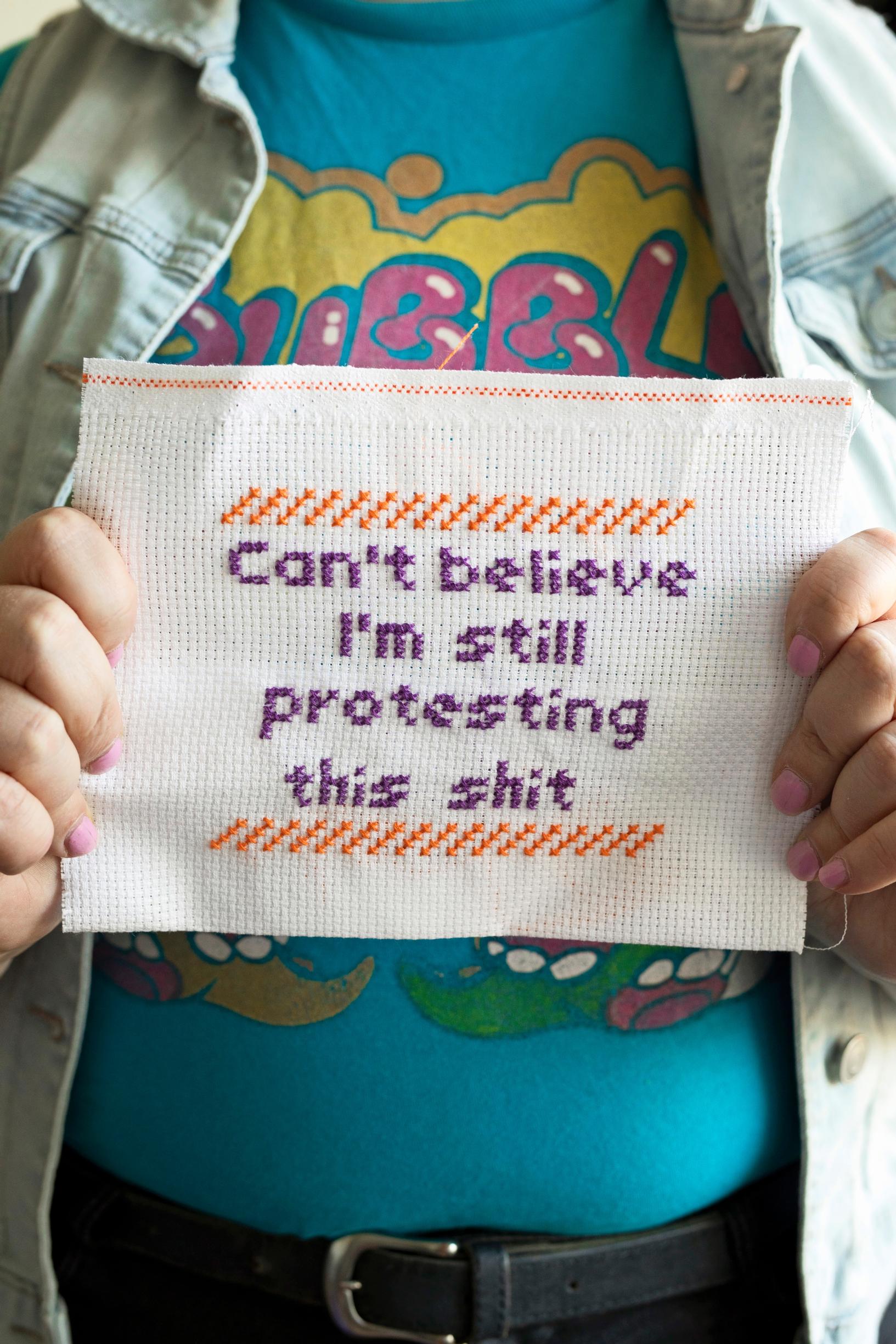

The radical aspect of our activity is the fact that we don’t stick to instruction manuals, but everyone gets to make whatever they want. At the same time, the works can make a statement. Crafting is a gentle way to criticize norms and practices. I myself have used my works to comment on issues like body norms and gender stereotypes.

Above all, Radical Cross-Stitch is a great way to come together. In that way, the activity parallels the sewing circles of old times. They were gathering places where people could talk about societal and personal matters in a safe environment.

When I first got involved, I hadn’t done crafts in years. But I soon realized that I’m pretty good at cross-stitching. It’s a simple and approachable technique that allows you to quickly make something of your own.

For my first work, I used a ready-made cross-stitch pattern featuring a bunny. I added the text ‘Bunnies not Nazis’ to it. Gradually, I realized that I could also use my creativity in my works. That’s how my style started to go in a more political direction.

Some hobbyists want to create empowering and encouraging cross-stitch works. In my works, a recurring theme is societal anger. I criticize social norms. My pieces are fairly sarcastic and negative.

Cross-stitching is a good tool for processing angry thoughts. Working on a piece physically as the idea takes shape on the fabric helps me to process it and let go.

I don’t do cross-stitching alone at home but only during meetings with others. At those meetings, I also share my thoughts with others. This is somewhat therapeutic too. Sharing feelings is relieving.

“Cross-stitching is a good tool for processing angry thoughts. Working on a piece physically as the idea takes shape on the fabric helps me to process it and let go.”

I’ve made cross-stitch pieces as gifts for my friends and family members. In addition to wall hangings, I’ve embroidered texts onto canvas bags and clothes. I’ve also worked with a bigger group of people to make cross-stitch graffiti on commission. You can make them by stitching with thin fabric pieces onto chain-link fences or chicken wire, which is then attached in place with zip ties.

I’ve also considered making a cross-stitched demonstration banner for protests. The message should be something that fits various occasions. Maybe I could stitch a huge ‘NO’ onto a large piece of fabric.

30% of Finns embroider at least occasionally. Historically, embroidery was a form of cultural folk art in various communities, and embroidered patterns and symbols had precise meanings.

Laura Penttinen, 39, Helsinki: “When I mend clothes, I can see how consumption decreases”

Ecological sustainability is an important value for me. I strive to consume as little as possible. For years, I’ve bought my clothes secondhand, and we don’t have a single piece of furniture bought new at home. However, I often feel that I can’t significantly influence how our current lifestyle affects the ecosystem. Watching from the sidelines makes me feel helpless and distressed. If I can’t channel it into something, it turns into anxiety.

I don’t attend many demonstrations because I experience large crowds intensely, and it can start to overwhelm me. But I do want to make a difference. For me, crafting and writing are good ways to do that. They are quiet but by no means silent.

“I mend my clothes visibly whenever I can. I want to normalize taking care for your clothes.”

In school, crafts was my favorite subject. When I grew up, I didn’t make things with my hands so often anymore. Still, every year I knitted something.

With the onset of the coronavirus, my craftsmanship resurfaced strongly. I wanted to learn different techniques better, and I began pursuing basic studies in crafts. I became interested in mending when the Finnish Crafts Organization Taito chose patching and darning as the craft techniques of 2021.

I started looking for information and inspiration for repairing on Instagram. I found Finnish and international repairers with various hashtags like #visiblemending and #paikkaaminenjaparsinta (‘patching and darning’). One of the first garments I repaired was my boyfriend’s old sweater. It had about twenty holes because of his skateboarding hobby. I learned different darning techniques while repairing them.

At the beginning of 2022, I started posting my own repair works on Instagram. Around the same time, I noticed a Helsinki-based repairer mentioning the idea of a repair café in their post. People could come there to mend their own clothes together with others.

It didn’t take long before we started monthly gatherings in a free-use space in a shopping center. Our Korjauskaupunki (‘Repair City’) community has now been meeting every month for a year and a half. We learn about repairing and other sustainable lifestyle choices from each other.

The repair community gives me a sense of security and belonging. I also get to see how consumption decreases and the world becomes a bit more whole one garment at a time. Every piece of clothing saved from the trash and returned to use is one less in the textile waste piles—one of which, I’ve heard, is visible from space on Chile’s deserts. It feels like I’m doing something concrete and meaningful.

“Slow crafting is at odds with the idea that we should constantly perform, consume, and be productive.”

I repair all my clothes, starting from wool socks. I haven’t darned cotton socks yet, but then again, I’m planning to darn my torn dishcloth next.

I mend my clothes visibly whenever I can. I think that like this, I can normalize taking care for your clothes. I hope it makes someone else think, ‘You can do this too.’

Making crafts itself is slow and contemplative work that requires time and space. Such activity is at odds with the idea that we should constantly perform, consume, and be productive. For me, craftivism is, in addition to consumption criticism, a statement in favor reflection and of a slower pace of life.

68% of Finns patch or darn their clothes. Repairing extends the life of a product and reduces textile production and textile waste.

Kaarina Heiskanen, 65, Äänekoski: “My knitting brings out the anger over how poorly people can be treated”

I do things that I know are right. Defending asylum seekers isn’t very popular work, and you’ll have to face many waves and splashes head-on doing it. I’ve been told I’m a suvakkihuora (‘overtly tolerant whore’) and an old cow, but to me, it doesn’t matter.

I knit mittens that make a statement. One of my designs says “Make human rights great again,” and another “I love human rights.” I sell them on social media and donate the money to charity.

Currently, I’m raising funds to support a family reunification project for an Afghan man. The bureaucratic wheels are dry and creaky, and reuniting a family costs a heck of a lot of money. I’m trying to do my part.

Sometimes knitting mittens is very mundane. If someone has ordered a pair as a Christmas gift, I make them in a terrible hurry. At the same time, knitting them still brings up anger over how poorly people can be treated.

“I was so incredible restless and full of frustration and anger. I decided to ground myself by knitting mittens.”

My awakening happened in 2015. There was a group home established in my hometown for unaccompanied minor asylum seekers. It was the first time I encountered people who had come to a foreign country with just a backpack and sandals on their feet face to face.

I started collecting donated items for these young people. On two evenings a week, I held Finnish language conversation circles for them. I also got to know others who help asylum seekers on Facebook. Through this, I learned how badly the asylum processes are flawed and how the legal protection of asylum seekers wavers.

A year later, I watched as the Afghan boys I had come to know turned eighteen and were moved from group homes to reception centers without any support. I saw their worries and fears when they didn’t know what would happen to them.

I was so incredible restless and full of frustration and anger. I decided to ground myself by knitting mittens.

I wouldn’t call myself a craftsperson otherwise. When my children were small, I sewed clothes for them, and when I was younger, I did knit mittens. I liked patterns and knew how the patterns in traditional Finnish and Estonian mittens had their own indirect messages.

In the same way, crafts have always had something in them that you can’t necessarily read directly. There are hidden messages in signs and symbols. I thought that the messages could be written out more clearly.

I hadn’t knitted for years, but I certainly had the tools in my cupboard. I designed mittens that said ‘Keep calm and help the refugees’ on graph paper. They convey that no one needs to be frightened of shadows; instead, we calmly follow human rights agreements and treat all people as people should be treated.

In the same year, I used this pattern to knit blue-and-white versions decorated with Finnish flags. I sent them and a letter to all the presidential candidates before the 2018 election.

Nowadays, I have a few different mitten patterns that I knit continuously. The newest of these is my Minna Canth’s Day design from 2023, which reads ‘I couldn’t care less about what people say.’

25% of craft hobbyists engage in crafts, DIY, or building because it’s therapeutic. For 37 percent, it represents creativity and self-expression.

Source of the figures: Crafting in Finland survey, Finnish Crafts Organization Taito and Taloustutkimus, 2021