Plagiarism or just a storm in a teacup? Five famous copying controversies from Finland

From time to time, allegations of copying make headlines, and even major design companies have been targeted. What’s really behind these accusations, and were they justified?

Copying controversies have been surfacing at a growing rate in the design world. When multiple designers follow the same trends and take inspiration from each other’s creations, it’s likelier that similar products will appear on the market. Are these accusations justified?

“Often these plagiarism controversies are storms in a teacup, so to say, mainly because people don’t fully grasp what intellectual property rights are and how they apply to design,” says fashion law postdoctoral researcher Heidi Härkönen from the University of Turku.

What constitutes crossing the line when it comes to similarity can differ greatly between designers and the law. Beyond intellectual property rights alone, it may be more fruitful to discuss broader industry practices. Another issue altogether is the cheap knockoffs of well-known furniture and décor items, typically manufactured in Asia.

Härkönen suspects some instances of copying remain undisclosed. Finland’s design scene is small, and up-and-coming designers may hesitate to accuse a would-be employer for fear of being labeled difficult.

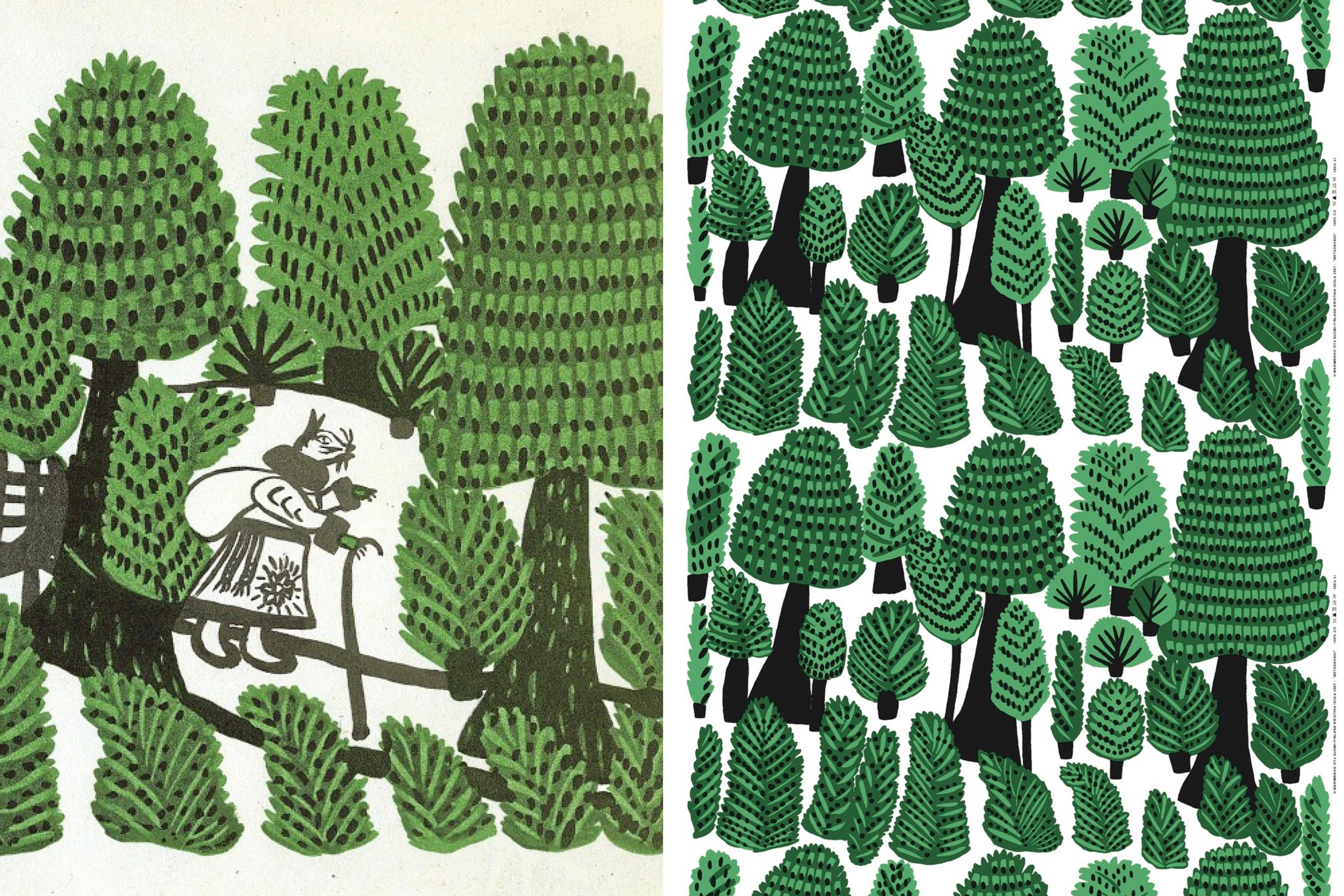

1. Marimekko’s Metsänväki copied a children’s book

Marimekko’s 2013 plagiarism case is often dubbed the mother of all copying scandals. Kristina Isola designed the Metsänväki pattern for Marimekko in 2007, and it was nearly identical to illustrations by famed Ukrainian folk artist Maria Primatšenko for the book Rotta matkalla. The tree trunks and branches appeared exactly as in the original, minus the rat family.

A private art enthusiast recognized the 1963 illustration, exposing the copying. Isola confessed to copying and admitted acting improperly. She explained that she hadn’t considered she was appropriating someone else’s creative work—or copyright at all. Marimekko ended its decades-long relationship with her and apologized publicly to the Finnish populace. By then, the Metsänväki design had already adorned, among other things, a Finnair airplane. The pattern was withdrawn.

Marimekko agreed to provide compensation before Ukraine’s Museum of Folk Art could take legal action. The matter was settled with Primatšenko’s heirs. Five years later, Marimekko sponsored a large-scale Maria Primatšenko exhibition in Turku.

Several more scandals quickly followed. Marimekko faced renewed scrutiny when British publisher Random House began investigating whether its Isoisän puutarha pattern was copied from a children’s book.

A designer’s ethics also raised questions when it emerged that Maija Louekari had used a 1960s photo as a basis for Marimekko’s Hetkiä fabric. This was allowed, though, because Louekari produced her own creative interpretation of the photo.

Moreover, in 2008 Marimekko sued the Italian label Dolce & Gabbana. One of its prints strongly resembled Marimekko’s Unikko design. Ultimately, Dolce & Gabbana agreed to pay damages for using the pattern.

Maija Isola’s Unikko design continues to turn up in infringing contexts around the world. In 2015, for instance, a flower pattern closely resembling Unikko appeared on items sold by the Aelia Duty Free chain. Marimekko stated it would address any unauthorized use of its trademark whenever possible.

In 2019, Ralph Lauren introduced a striped, long-sleeved dress that looked remarkably like a Marimekko garment. Despite the likeness, Marimekko did not pursue the matter.

2. A counterpart found for Iittala’s Play mug

In February 2024, the design community erupted over two round-handled coffee cups that looked strikingly similar. Iittala launched a brand overhaul—immediately drawing significant scrutiny—and simultaneously faced plagiarism accusations. Its new Play range included a coffee cup by Aleksi Kuokka, which strongly resembled a cup by ceramicist Johanna Ojanen. Ojanen’s mug had been on sale since 2011, including at Artek’s stores.

The designer of the disputed Play mug insisted he works from his own concepts. Iittala initially declined to comment, while its parent company Fiskars stated that the Play mug went through “thorough validation.” Citing the mug’s universality as a household object, they argued that various designs can look alike.

The following day, Ojanen revealed that Iittala had indeed been aware of the cups’ similarity. Iittala contacted her a few weeks before the launch, and she visited the company’s headquarters. Ojanen felt the meeting was positive and believed Iittala wanted to find a solution that would satisfy both sides. However, the company never followed up.

Ojanen did not say whether she thought the Play mug was influenced by her design. She felt she was left to face a social media backlash alone, while Iittala seemed to hide behind the claim of coincidence. She wished for a public acknowledgement from Iittala that the similarity was indeed noted.

Iittala admitted it was slow to respond publicly to the copying uproar. Its statement was unequivocal: the Play mug was not a copy, and the firm rejects copying of any kind. The break in communication with Ojanen was attributed to a misunderstanding. Although the similarity was spotted, Iittala decided to proceed with the launch because a copyright specialist concluded there was no infringement. Iittala said it would schedule a further meeting with Ojanen, but nothing additional was disclosed.

3. Makia’s print resembled a yacht club logo

In 2019, clothing label Makia Clothing was accused of copying. One of its collections featured a design with an M-shaped sail, a wave, and a seagull, looking very much like the logo of the Helsinki-based sailing club Merenkävijät, which dated back to 1923.

The sailing club requested that Makia cease using what appeared to be its logo. Makia conceded that it had referenced the logo but referred to its own version as a reinterpretation. According to media reports, Makia suggested the club see it as flattery.

The club was not satisfied. It insisted that Makia withdraw the products and pay 5,000 euros in damages to support its youth programs. Makia said no and offered 2,000 euros instead. It also asked the club not to discuss the matter publicly.

When the copying dispute made headlines the next day, Makia announced it would pull the items featuring the contentious design and would pay 5,000 euros to the club. The withdrawn products were donated to the sailing club, which intended to give them to charity. Makia, however, argued that referencing existing logos is common internationally and considered Finns overly sensitive regarding intellectual property.

The controversy did not end there. People soon pointed out other Makia prints allegedly resembling different club emblems. For example, the Helsinki paddling club Merimelojat’s logo—a wave and the letter M—looked similar to Makia’s Sight T-shirt. Makia stated that this logo did not inspire its design.

In December 2024, art student Heidi Vuorio claimed Makia had incorporated an image from her murals and prints: “Tonnin seteli”, a reference to the popular Finnish TV show Kummeli from the 1990s. Vuorio’s pieces portrayed Kummeli actor Heikki Silvennoinen in a brightly painted pop-art style. Makia countered that it had been unaware of Vuorio’s work when designing its print and described Vuorio’s art as more sophisticated than its own.

Design insiders reflected that Vuorio herself had taken cues from artist Risto Kajo’s Tonnin seteli (2020), and that the pop-art style itself had been in use since Andy Warhol.

4. Accusations against Kalevala Koru fell flat

In autumn 2024, numerous claims of copying circulated. One was aimed at Kalevala Koru. Jewelry creator Matilda Mannström believed the brand’s new Männyt range resembled her Souvenir d’Océan collection. She drew attention to similarities in form, look, and the adjustable clasp. The Männyt collection was designed by Ildar Wafin.

Kalevala Koru emphasized that it takes these matters seriously, as any form of plagiarism contradicts its values. It follows strict oversight in its design work and contacted Mannström for clarification. However, Kalevala Koru concluded that the pieces were sufficiently different overall and in their details, so it felt no copying had taken place.

Nothing more developed from the suspicion. Still, it generated commentary on channels like the Instagram account @vaindesignjutut, known for candidly exposing issues in Finland’s fashion and design scene.

Some people felt the matter was tenuous from the outset. Designers’ emotional attachments to their creations can cloud objectivity, they claimed. Many also attributed copying charges to limited familiarity with intellectual property law within the design community.

Fashion law researcher: copyright can allow two identical products

When two designers independently create, for example, the same kind of round-handled coffee cup, it could simply be that they’re following identical trends or aesthetics. Once copying accusations arise, opinion often turns to copyright. However, copyright may not actually apply in these situations, explains fashion law postdoctoral researcher Heidi Härkönen.

Copyright is the intellectual property right most familiar to the general public but is often misunderstood. A design object can be protected by copyright in much the same way as a work of visual art or literature.

To qualify for copyright, the creator must engage in “mental creation,” and signs of their free and creative choices must be visible in the final product.

“Copyright law focuses heavily on the bond between the designer and the work. It doesn’t matter how the piece looks to the wider public,” Härkönen clarifies.

Determining whether a piece qualifies for copyright can be complicated, Härkönen notes. Preliminary drawings and mockups can help document the creative process.

An obscure but real legal reality is that copyright allows what’s called double creation: Designers A and B can each independently craft nearly identical works, both protected by copyright, neither infringing on the other. The main question is whether the subsequent design was made independently. The law doesn’t require that a protected creation be one of a kind.

Design protection is the form of intellectual property that Härkönen believes is typically more relevant in copying disputes. If a product is unique and new, it automatically gets unregistered design protection for three years. For longer coverage, the design must be registered.

“Often, designers only consider registering their designs once it’s too late,” she says.

In the public debate over Iittala’s Play mug, many points relevant to design protection surfaced. However, they were moot because the first mug had not been registered, weakening any infringement claim.

Under design protection law, the designer’s personal style is less crucial than it is under copyright law.

A trademark is yet another type of intellectual property. It provides exclusive rights to a mark and any mark that risks confusion with it. People often conflate these three forms of IP.

Take Dolce & Gabbana vs. Marimekko over the Unikko print, for instance. Marimekko had a strong position because Unikko was a registered trademark. The company could argue that D&G’s pattern could be confused with its own.

With a registered design and a trademark, all is spelled out. In contrast, copyright disputes hinge on whether copyright exists in the first place.

5. K-Rauta’s donut-shaped candles raised suspicions

In December 2024, Finnish social media influencer Janne Naakka accused the retail company K Group of copying a candleholder designed by his brand, Naag Living. Both pieces resembled two stacked donuts, matched in thickness, and even shared the name Donitsi (“Donut”).

Conceived by Naakka and designer Hannakaisa Pekkala, Naag Living’s ceramic candleholder included a perceptible gap between the two donut forms. It went on sale in July 2024. K Group’s hardware store chain K-Rauta’s plastic LED candle appeared three months later. Naakka doubted it could be a coincidence.

The K Group denied plagiarism. It said K-Rauta had placed its order with a Chinese factory as early as February 2024, making copying impossible. The K Group also stated it was unaware of Naag Living’s product or its name. After Naakka’s attempts to contact the K Group went unanswered, he decided to go public. Naakka told Avotakka that he had proposed a partnership before the K Group’s product was introduced, supplying photos of his candleholders.

Online commentators noted that donut shapes are a hot trend. Comparisons emerged, for instance, with Laura Väre’s wooden Donut candleholder. Naakka also cited a Gina Tricot candle sporting a similar style, which he distinguished from using the exact same form.

Plagiarism or not?

How do we determine whether two similar items amount to plagiarism?

“Plagiarism doesn’t have any legal meaning at all,” Härkönen notes, to many people’s surprise.

In copyright, the correct term is copying. As Härkönen puts it, a copy is a copy if it is actually a copy. Evidence must exist that copying occurred. For instance, Marimekko’s Metsänväki was straightforward, as the copying was acknowledged. Whenever there’s doubt, a court decides.

To head off legal disputes, it’s best to secure design protection. Then nobody has to prove copying; a violation may be established if someone with relevant knowledge sees the two objects as having the same overall impression. Such an informed user is neither an expert nor a layperson, but more like a Avotakka reader with an interest in design.

In trademark law, infringement occurs when another product or symbol can be confused with the existing trademark.