Antti and Vuokko Nurmesniemi—an award-winning design duo with a shared vision

Impulsive Vuokko and deliberate Antti Nurmesniemi found each other during their student days. The Finnish power couple went on to become award-winning designers and advocates of sustainable design.

Vuokko Eskolin left Töölö Coeducational School at 16 and decided to devote herself to artistic work. In 1946, she applied to the Central School of Art and Design, known as Ateneum, but its artistic director Arttu Brummer still felt she was too young and inexperienced. Having grown up in Helsinki’s Kallio district, Vuokko spent the following winter studying at Ateneum’s evening school.

Around the same time in 1947, a native of Hämeenlinna who was three years older than Vuokko, Antti Nurmesniemi, also applied to the Central School of Art and Design. He was passionate about building model airplanes, and films. He had dreamed of becoming a documentary film director but decided to apply to Ateneum instead.

Antti’s simple interior completely charmed Vuokko.

Vuokko Eskolin and Antti Nurmesniemi began their studies at the same time in fall 1947: Antti in interior and furniture design, and Vuokko in ceramics. Alongside her ceramics studies, Vuokko attended a three-year dressmaking program at the Helsinki Cutting School, where she learned to draft basic patterns and fit garments.

Their shared journey began during their studies, when Antti invited Vuokko to his home in the Laajasalo district in Helsinki. Antti had rented a small room on the ground floor of an old single-family house, while upstairs lived interior architect Olli Borg and his family.

Antti’s simple interior completely charmed Vuokko. She says that he had already mastered the art of simplicity, and his understanding of design influenced her from the start. Vuokko and Antti quickly felt a strong connection and spent much of their time together. Vuokko’s fellow student Liisa Hurtta wrote, “Vuokko is in love and out of her mind!”

Working around the clock

Antti graduated as an interior architect in 1950, and Vuokko, after a prolonged illness, graduated two years later as a ceramist.

They both worked during their studies—Antti in the Stockmann drawing office and Vuokko in small ceramics workshops around Helsinki, as well as at the Arabia factory. Once graduating, Antti joined architect Viljo Revell’s firm, and Vuokko opened her own ceramics studio. They got married at the chapel of Helsinki Cathedral in 1953 with only the closest family present.

Antti got his dream project when Revell’s firm—after winning an architectural competition—designed the Teollisuuskeskus building on Eteläranta, also known as the Palace Hotel.

Antti was in charge of designing the building’s sauna facilities and furnishings, which led to acrylic balcony chairs, large lounge chairs for the reception area, and wooden sauna stools. This stool became his most famous piece of furniture, a distinctive merger of modern design and tradition.

Antti’s involvement in the Palace project was also a turning point for Vuokko’s career. During construction, Antti met co-founder of design house Marimekko, Armi Ratia, who had a small sales office on the top floor of the Palace. Armi had heard from Borg and Brummer about Antti’s remarkable girlfriend, a ceramist who also sketched fabric prints. Vuokko was invited to meet Ratia. She was asked to create a fabric that imitated the tiny, mosaic-like Oomph motif designed by Finnish-born, Sweden-based textile artist Viola Gråsten.

Vuokko’s answer to Armi’s request was the bold, wide-striped Tiibet fabric, drawn by hand at full scale. Her unique, daring vision impressed Armi, and their collaboration began right away.

The Nurmesniemis' first joint exhibition was held in 1957 at Artek's gallery space in the Rautatalo building in Helsinki.

Vuokko closed the ceramics studio she had opened the previous year and immersed herself in intense work at Marimekko. In addition to designing fabrics and clothing, she soon planned exhibitions, fashion shows, window displays, and poem-like advertisements.

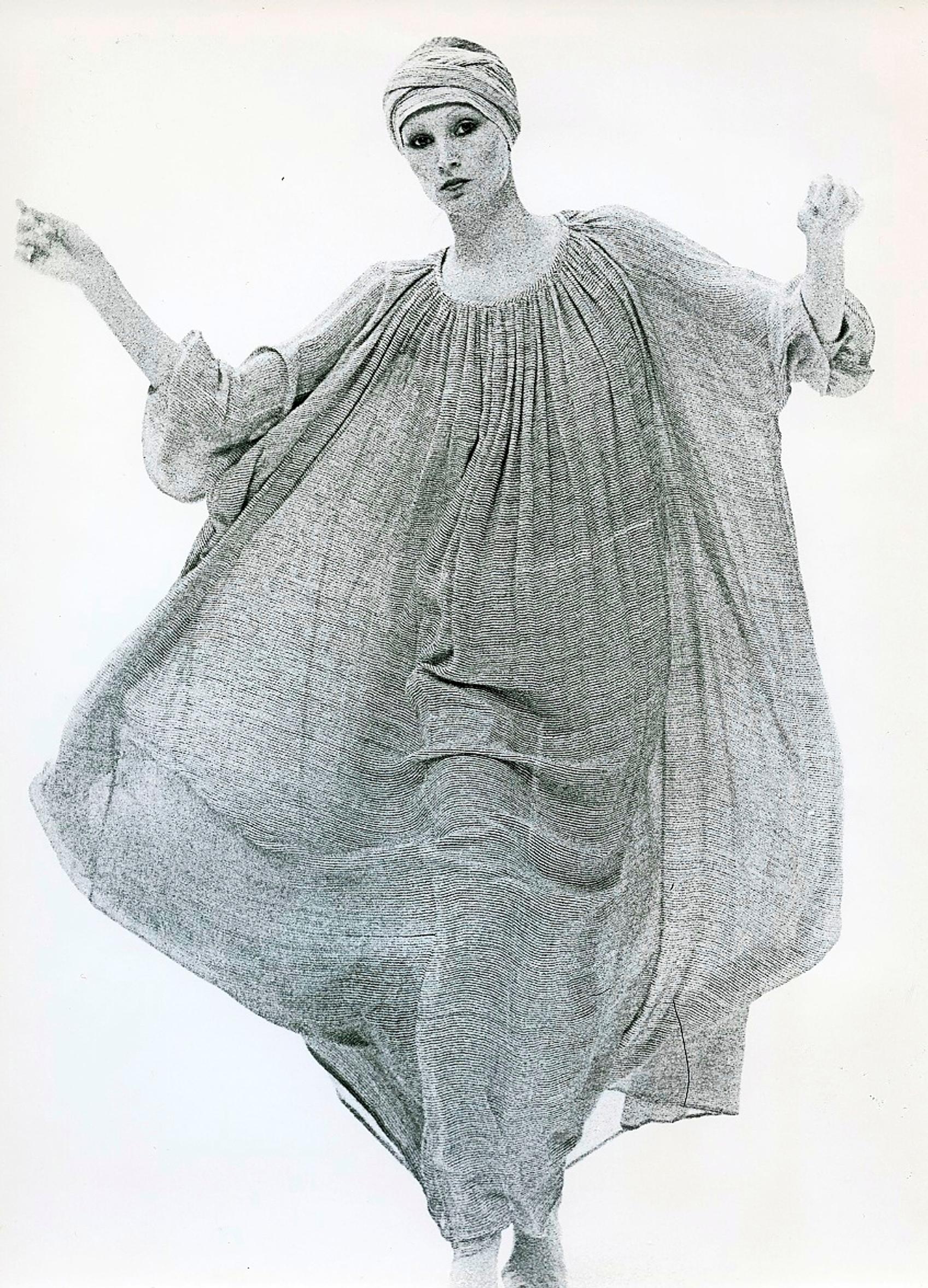

They labored around the clock, and Vuokko produced numerous designs that became classics. Among her most famous works are the Iloinen takki, also called Kihlatasku, and the Jokapoika shirt featuring the Piccolo pattern, which has been in uninterrupted production for 66 years.

Several fabrics designed by Vuokko in the 1950s are still featured in Marimekko’s contemporary and interior collections today.

The Nurmesniemis were in constant dialogue and inspired each other’s professional growth.

Seamlessly together

Meanwhile, Antti thrived as an interior architect and established Studio Nurmesniemi in 1956. Their first joint exhibition was held in 1957 at Artek’s gallery space in the Rautatalo building in Helsinki. Antti showcased lighting, furniture, and cast-iron objects, while Vuokko displayed fabrics, ceramics, and glass. Antti’s Pehtoori and Pikku-Pehtoori pots for Wärtsilä were unveiled there for the first time. Vuokko’s fresh, vibrant color choices gave the pots their distinctive appearance.

In the following decades, they held joint exhibitions in places like the Netherlands, Iceland, and Japan, always striving for a unified, streamlined display.

Although each pursued their own career, Vuokko and Antti’s styles blended seamlessly. They were in constant dialogue and encouraged each other’s professional growth. Their marriage was founded on equality, and both took pride in one another’s achievements.

They embraced a bold, uncompromising creative way of life early on. Working with different materials, they produced designs that complemented each other yet were distinct in style. They both championed good, enduring design in Finland and abroad.

Their working habits and personalities differed: Vuokko was impulsive and fiery, while Antti was calm and careful.

The Nurmesniemis rank among the most acclaimed Finnish designers.

Their joint creativity produced successful striped-shirt-themed wallpaper competition entries beginning in the 1950s. In 1964, they entered the Milan Triennial competition for Finland’s section, themed Leisure, taking first and third place.

Vuokko and Antti designed the show space with Matti A. Pitkänen’s large nature photographs. A hand-carved boat from the Savonia province in Finland also drew attention.

Antti had already designed Finland’s section for the previous Milan Triennial in 1964. Throughout his career, he contributed to many major design exhibitions, the largest of which was called Design from Scandinavia, a nearly year-long traveling show in Australia.

Traveling the world

In August 1959, Antti Nurmesniemi received the highly regarded Nordic Lunning Prize. That same year, Marimekko successfully participated in a Finnish applied arts exhibition in Boston, making Vuokko an overnight sensation in the American press. In turn, the First Lady of the United States, Jacqueline Kennedy acquired eight Marimekko cotton dresses designed by Vuokko.

Using Antti’s Lunning Prize money and additional loans, they traveled to India together for three months.

Vuokko remains grateful that Antti wanted to experience India’s vibrant culture by her side. Shortly before leaving, Vuokko decided to part ways with Marimekko for good.

According to Vuokko, that trip was the journey of their lifetime, even though by the standards of the 1950s they had already traveled extensively, and would continue to do so in the coming years.

The Nurmesniemis traveled widely, together and separately. On their shared trips, they always made time to explore local architecture, design, and art.

After returning from India and leaving Marimekko, Vuokko maintained a low profile for three years. In 1964, she made a significant comeback, launching her own company to instant acclaim.

Vuokko’s minimalist designs and striking, graphic prints won wide praise. She opened her Vuokko Oy shop on Merikatu in Helsinki, which Antti designed. That same year, she also received the Lunning Prize.

The Nurmesniemis rank among the most acclaimed Finnish designers. Both have been honored with an esteemed honorary membership in England’s Royal Society of Arts.

Vuokko stayed busy running her company and designing, while Antti focused on his interior architecture office, leading interior design projects, product and furniture design, exhibition concepts, and roles in design organizations. Between 1956 and 1999, his firm handled over 300 interior projects, including the State Guest House in Munkkiniemi, Finland and Finland’s embassy in New Delhi, India. Antti was respected as both a supervisor and a person.

The Nurmesniemis were a warm and welcoming couple whose parties and dinners were always delightful.

A studio home by the Gulf of Finland

In 1975, a studio house designed by Antti was completed along the Kulosaari shoreline, combining the couple’s home and Antti’s office under one roof.

Clad in natural-toned pine paneling, the house is spacious and bright. It is cozy yet perfect for hosting gatherings, and it mirrors its inhabitants and their design ethos.

Guests were a big part of Vuokko and Antti’s life. Both had many friends and collaborators. The Nurmesniemis were a warm and welcoming couple whose parties and dinners were always delightful. They became like design ambassadors for Finland, promoting the country’s design worldwide.

Vuokko and Antti remained very close until the end. After Antti’s passing in 2003, their mutual friend Nasir Kassamali visited Vuokko in her grief at Kulosaari and remarked that he had never witnessed such a deep love story.

The story of Vuokko and Antti is also a key part of Finland’s design history.